It’s 2030 and the workweek is just 15 hours. Tech advancements have increased productivity to the point that 3 hours of work per day is enough to maintain society, and we dedicate the rest of our time to leisure. At least, that’s what economist John Keynes predicted back in 1930 in his famous essay “Possibilities For Our Grandchildren.” Now, almost a hundred years later, how are Keynes’s grandchildren doing?

Technologically, we’ve more than met the requirements. From assembly lines to artificial intelligence, each leap in automation has promised to free workers from mundane labor and usher in a new age of creativity, rest, and abundance. But instead of leisure, we’ve found ourselves trapped in a paradox: more tools and faster systems, yet we’re working more than ever.

The very systems designed to save us time seem to have created a new kind of pressure: to produce more, scale faster, and be constantly available. Whether you’re in a corporate job or working in a warehouse, the message is the same: optimize or fall behind.

Ironically, today’s AI rush flips Keynes’s vision on its head. New automation tools and AI agents are used for creative work like writing, creating images, and editing videos, while heavy work such as packing heavy boxes and moderating content are still the responsibility of humans.

This article explores how we got here. We consider whether automation is really making us more efficient, or if it is not-so-quietly tightening the grip of control. And more importantly, what would it take to break the cycle and reclaim time on our own terms?

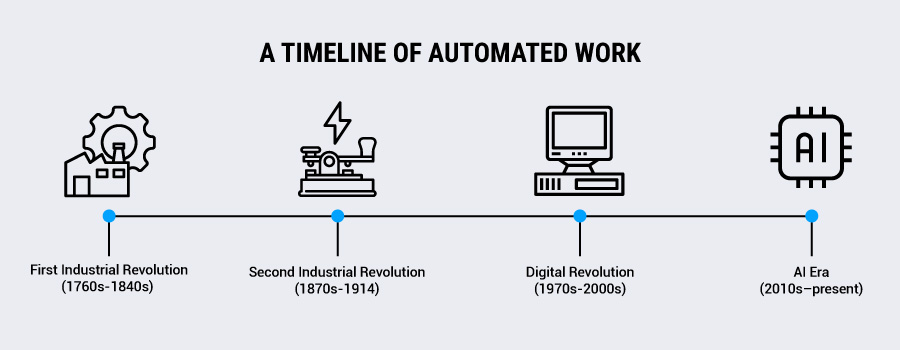

A timeline of automated work

Before digital workflows, automation on the factory floors was powered by steam, coal, and later, electricity. Here’s a short timeline of how the automation of manual labor has progressed through the years.

- First Industrial Revolution (1760s–1840s): Steam engines, mechanized looms, and coal‑powered factories shifted production from small cottage workshops into larger factories in cities. Automation multiplied output, cut costs, and made everyday goods more widely affordable, but also confined workers to strict shift schedules.

- Second Industrial Revolution (1870s–1914): These decades brought us electricity, railroads, and the telegraph. Division of labor and mass production models like Ford’s assembly line in 1913 optimized repetitive factory work, significantly cutting down on production time.

- Digital Revolution (1970s–2000s): The end of the 20th century ushered in the arrival of personal computers and software. The internet began automating administrative, analytical, and information-based tasks. It cut down on filing, communication lag, and data processing — the core functions of knowledge work.

- AI Era (2010s–present): With machine learning, large language models, and generative tools, automation now targets cognitive and creative labor. From copywriting and coding to image generation and research synthesis, automation now spans creative disciplines.

Each new wave builds on the last, expanding the scope of what machines can do for us. From physical to digital to now cognitive labor, we’ve progressively outsourced more human effort. With each burst in development, the promise stays the same: work less, live more.

What has also stayed consistent, however, is this: workplace expectations evolve in tandem with automation. Instead of freeing workers up, these tools often became a means to squeeze more output from the same hours.

The hours we “save” are reinvested in new KPIs and higher demands around productivity. As efficiency goes up, expectations follow suit and the dream of working less is yet again postponed.

Most recently, the mainstreaming of AI tools brought that promise into creative and knowledge work. According to Asana’s 2024 State of AI at Work, daily generative AI users were 89 percent more likely to report productivity gains compared to casual users.

But adoption comes with a price. The same report found that 26 percent of workers worry their peers will consider them lazy for using AI, and 23 percent fear being seen as frauds. This points to a cultural bias against ease that reinforces the idea that legitimate work must “look hard,” even when it isn’t. Effort becomes performative, while real value such as insight, strategy, and voice stays invisible.

And while AI promises time savings, it also creates new labor needs. From off-brand phrasing, to writing choices widely viewed as “AI tells,” to hallucinations that can even lead to legal issues, much of the automated work ends up needing a fix from human hands. As Prof Feng Li, associate dean for research and innovation at Bayes Business School, notes, “Poor implementation can lead to reputational damage and unexpected costs, often requiring rework by professionals.”

The two sides of automation: efficiency and control

As the Asana report demonstrated, automation-powered productivity can lead to suspicion. When workers start worrying more about the perception of work ethic than the quality of their output, it reflects a deeper shift in workplace values. It signals that the organization has moved away from purpose and toward performance.

Although this culture of performing busyness isn’t new, digital work has intensified it. The rise of remote and hybrid setups in the wake of the pandemic has blurred the lines between work and time off.

According to a Gallup study from 2023, 44 percent of remote workers said it was harder to disconnect from work compared to being in-office, and 71 percent of knowledge workers reported checking work notifications outside of business hours. Think Slack pings after dinner, email replies on the weekend, and Google Calendar blocks just to show you’re busy.

Meanwhile, the very tools sold as productivity boosters are increasingly used for employee surveillance. There’s even a name for that, too: bossware. Gartner reported that over 70 percent of large companies have adopted some form of “bossware” to monitor productivity, from keystroke tracking to webcam monitoring.

Automation meant to streamline work ends up reinforcing a climate of constant visibility, in which appearing productive becomes just as important as being productive.

But the optics of work is only one of the deeply ingrained values still keeping us away from Keynes’s optimistic predictions. It’s clear that balancing labor, time, and leisure is more nuanced than just the choice of which tech stack to use.

Who benefits from automation?

Technology is not created in a vacuum. It results from the intentions of its creators and reflects the zeitgeist of when it was developed. And in most corporate contexts, tools are adopted not to reduce hours, but to increase margins.

Take the case of warehouse logistics. Amazon famously uses algorithm-driven schedule optimization to manage labor at scale. Workers wear wrist devices that track movements, tempo, and even idle time. Here, automation enables granular oversight and hyper-efficiency, and is not designed to optimize for human well-being.

Even in white-collar sectors, the benefits of automation aren’t distributed equally. According to Asana’s State of AI at Work 2024 report, leaders are 1.6x more likely than individual contributors to say AI is saving them time. The same tools that theoretically empower everyone more frequently amplify the efficiency of the already-powerful, leaving others to adapt, requalify, or be displaced.

Fidji Simo, CEO of Applications at OpenAI, acknowledges that impact in an open letter shared on the company page. “Every major technology shift can expand access to power—the power to make better decisions, shape the world around us, and control our own destiny in new ways. But it can also further concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few—usually people who already have money, credentials, and connections.”

Automation isn’t inherently good or bad: it’s a system. And like any system, power dynamics are embedded within it. So the real question might not be “what can automation do for us?” but rather: who gets to decide what it’s designed to do, and what it learns about us along the way? Because, especially when it comes to AI, what automation knows — such as our habits, preferences, and patterns — is increasingly shaping what it does, and who it ultimately serves.

Privacy in the digital age is shaped by the technology we use daily. From the beginning of the internet to AI-driven platforms, digital architecture often governs privacy more than legislation.

Beyond doom and gloom

While it’s easy to frame automation as a source of anxiety or loss, that’s only half the story. Even as digital systems reshape work and daily life, countless examples illustrate how thoughtfully applied technology can enhance human well-being, foster creativity, and empower individuals, rather than simply optimizing them.

“That’s why we have to be intentional about how we build and share these technologies so they lead to greater opportunity and prosperity for more people,” explains Fidji Simo. “The choices we make today will shape whether the coming transformation leads to greater empowerment for all, or greater concentration of wealth and power for the few.”

Here are a few real-world examples where automation is being put to good use:

Healthcare

AI-driven diagnostic tools now analyze medical images with near-perfect accuracy. These tools improve and speedup diagnoses while reducing mistakes. AI tools are also helping doctors provide more personalized treatment plans and identify early risks using predictive analysis.

Accessibility

Advances in AI-powered accessibility solutions like automatic alt-text, real-time captioning, and voice recognition are making the digital world more inclusive. For example, Microsoft’s Seeing AI supports visually impaired users with object recognition and text narration to help them navigate the physical world around them.

Agriculture

AI-powered systems are transforming agriculture by giving farmers real-time insights about their crops. Intelligent irrigation systems use AI algorithms to monitor soil moisture and weather, then automatically deliver the optimal amount of water to each field. These technologies help detect leaks, optimize resources, and improve crop yields while reducing water waste.

Language preservation

AI tools are being used to help preserve endangered languages. Google’s Woolaroo project uses AI-powered image recognition to help Indigenous communities teach and learn their native tongues. Users can point their phone cameras at an object, and Woolaroo will translate and pronounce the object’s name in the user’s chosen language, from Māori to Louisiana Creole.

Cultural countercurrents

Not everyone is sold on tech permeating every aspect of modern life. Several movements that go against the grain of excessive automation are gaining popularity. In the groups outlined below, people gather in person to rethink their relationship with their tech devices, or simply to create pockets of slowness and presence.

Many of these movements are also choosing experiences that are slower, more present, and under less surveillance. In-person gatherings and analog hobbies don’t generate behavioral data. You get to participate on your own terms, without the pressure to perform or of being watched. In their own way, these choices echo the deeper values of consent, boundaries, and autonomy that the digital world often forgets.

GenZ goes Luddite

A growing number of Gen Zers are rethinking how and when they engage with technology. They’re using it intentionally for what’s needed, and opting out when it’s not. Groups like the Luddite Club in New York City reject social media in favor of analog hangouts, while many others turn to dumb phones or offline hobbies as a way to carve out space for presence and real-world connection.

Analog revival

Vinyl record sales keep rising year-over-year and film cameras are back in fashion, as are print magazines and even cassette tapes. Companies like Polaroid and Field Notes have built thriving modern businesses around tactile, offline experiences, which seems to reflect a growing desire for screen-free creative outlets.

Offline events

After the online event saturation catalyzed by the pandemic, there has been a push to return to face-to-face events that urges people to stay away from technology altogether. Communities such as The Offline Club are spreading all over Europe, inviting members to be off their phones and reconnect with themselves and their forgotten hobbies. Similarly popular are book club-like events, where people gather together to read in silence.

Privacy shapes how we’re seen, how we trust, and how we grow. In an era of algorithmic noise and eroding trust, reimagining privacy as a human need is key.

Breaking the cycle

If the current trajectory of automation has led us to endlessly busier schedules and surveillance in the name of productivity, it’s time to ask: what would it look like to design automation differently?

A human-centric approach to automation would require us to redefine our values. Instead of measuring productivity in hours logged or outputs delivered, what if we saw time itself as a new metric of value: more than just the time spent working, but also the time regained for rest, learning, or connection?

Prioritizing time is not an imaginary utopia; some companies are already pioneering the shift. One of those is Basecamp, the self-proclaimed down-to-earth project management software company. They are known for their contrarian take on work culture, having made “calm productivity” their business motto.

Unlike Silicon Valley giants chasing scale and speed, Basecamp limits its employees to a fixed workweek, prioritizes async communication, and works in 6-week cycles instead of sprints. Their values are reflected in their product: automations in their software are not meant to maximize user engagement but to streamline repetitive tasks and protect focus.

Instead of just talking about work-life balance, Basecamp intentionally designed the conditions for that balance to emerge. In doing so, they’ve created a clear example of what it can look like to use automation to respect users’ time.

Reclaiming the dream of leisure, learning, and community

Nearly a century ago, John Maynard Keynes imagined that technological progress would shrink the work week to just 15 hours, leaving the rest of our time for leisure, learning, and community.

That future hasn’t materialized. Instead, the time-saving tools we’ve built are more often repurposed to maximize output and create more work, not freedom.

Course correction is still possible, though. Human-centric automation offers a path forward. More than just tools that eliminate repetitive work, we can embrace a mindset that redefines how we measure productivity. That includes valuing focus over constant availability and using data to empower, not exploit.

If we don’t define and assert our values as technology and work evolve, Big Tech will do it for us.

This isn’t just about individuals using tech responsibly, but also about how entire organizations can adopt these values. Internal principles that are privacy-first and consent-driven principles can create the kind of work culture that actually supports deep work and respects boundaries.

That means clearer communication norms, opt-in collaboration instead of performative busyness, and systems designed for trust, not surveillance.

The future Keynes imagined is still within reach. But reclaiming the 15-hour dream that centers leisure, learning, and community doesn’t just mean clocking fewer hours. It means building the technological, cultural, and organizational systems that protect what we decide what time is for.