I was scrolling pretty mindlessly through Instagram when the algorithm went super meta, and served me up a clip (8:12–9:42) —a quarter of a century old now — of Jeff Bezos being interviewed by Bob Simon on 60 Minutes.

Bezos was talking about how his new and exciting business, Amazon.com, could make a book recommendation to you, based on nothing more than what you’ve previously purchased. Watching it in 2025, the conversation between them is nothing less than extraordinary.

Bob Simon: “The computer also remembered my past orders, and compared me with other customers who’d bought the same books, it calculated which new books I might like too.”

Jeff Bezos:“That’s the data that allows us to try to predict what books and videos and music that you would like that you haven’t discovered yet.”

And there it is: The birth of the algorithm and the start of a journey that has fully reshaped society and almost every aspect of the way we live.

To an audience that fully grew up alongside such algorithms, and having experienced how they inform and co-author so many aspects of our lives, the excitement and wonder in this brief snippet of conversation feels beautifully naive now.

Watching it again is a good reminder of how far we’ve come, in such a short span of time — and an amusingly full circle moment, as no doubt its presence in front of my eyeballs was a result of the research I’d been doing for this article.

Algorithmic awe

Algorithmic recommendations — the sorting and matching — have been one of the defining elements of user experience in the last quarter century of online evolution. As the generation of vast volumes of data and information have been matched by increased compute power, these capabilities have become ever more present in our lives.

They have changed the ways in which we carry out the vast array of our day to day behaviours, helping to streamline, remove friction, and fundamentally —on the surface at least — make our lives easier and better.

Initially, this felt magical, opening up possibilities and turning on the taps of serendipity, discovery, and joy. In every aspect of our lives, if we showed the algorithm what we wanted, fed it our lives (our souls?) and it could hold up the mirror, reach into the belly of the beast, and play back what we wanted with extraordinary precision.

Algorithm as a feature

Whole business models sprang up on these capabilities, matching consumer desires with the consumer experiences offered to them. All based on ever greater dimensionalisation of both sides of the equation with the products and experiences that we were accessing, and also us, the consumer. Who are we? And what do we want?

Netflix, Spotify, Amazon, AirBnB, Tinder… These and many, many more emerging companies, — some of the biggest success stories of the last 20 years — rewrote whole categories, changing forever the way we buy, how we’re entertained, and even who we date.

Core aspects of our lives, broken down into elemental features. Like modern day alchemists turning lead into gold, but instead turning our preferences about music, shopping, and dates into lucrative subscription-based revenue models for big business.

You like songs with 80 bpm, and acoustic guitar sounds with piano and poetic lyrics? Sure, here’s 20 more artists and songs who match that description. Want to refine the details to hone in further on what you want? No problem, here’s another batch that matches the new preferences.

The same process has played out across every aspect of our lives. Whatever you wanted, it could be broken down into constituent parts, pattern matched against the whole landscape, and served back to you in real time.

Algorithm as a lifestyle

For a good decade, this algorithmally-driven way of life seemed to deliver wins all round. Consumers got more of what they wanted, brands could serve them more effectively and efficiently (and lucratively), and everyone experienced the mutual benefits.

“Recommendation as a feature” was front and centre, brought to the fore as a key brand or product benefit:

- People who bought that also bought this

- Because you liked that, you’ll like this

- Here are more people who match your preferences

The power dynamics felt empowering on the consumer’s side: being invited in, actively choosing things and experiences customized for you, and what you wanted to share. It felt good to be seen and part of an exclusive club.

The degree of personalisation was like nothing before, and extended to being able to connect with other people who shared the same wants, needs, and desires. The power of community that it facilitated only added to the seductive nature of it all.

At times, the experience felt like a new religion: personal data as daily prayer to the new tech gods of the 21st century?

Gradually though, the power dynamics shifted, and consumers started to notice that they were being driven by the algorithm, not using the algorithm to drive themselves. With maps, wayfinding, and occasionally self-driving cars, this has become a metaphor as writ large in real life as we’ve literally lost control of the direction of travel of our lives and the means to get there. We took our hands off the metaphorical and literal steering wheel.

Where previously we had to actively and consciously “feed” the algorithm by filling in forms and surveys and ticking vast arrays of boxes, it quickly turned to the algorithm passively training on our behaviours, not our active inputs. This subtle difference — the removal of friction — had some benefits, but fundamentally meant a loss of control and agency. We went from feeding the beast to being the food. From watcher to watched.

The devil’s in the detail

There was still no denying that this algorithmic rhythm to life brought many positive things, but the mood music started to change and the losses started to mount up — a tangible loss of control, destiny, happenstance.

The realisation hit that we were facilitating and succumbing to the commoditisation of everything, broken down into its constituent parts, to better serve the big spreadsheet in the sky.

Feed the algorithm. Offer up your soul and you too shall be repaid with the perfect miniseries, three-minute pop song, scatter cushions, or romantic partner. Mantras such as “If you’re not paying, you’re the product” took hold and with it came a greater focus on the impact of algorithms beyond the simplicity and frictionless ease they created.

And that’s just the commercial side. There have also been the more problematic aspects, including the accidental creation of echo chambers that have contributed to the polarisation of public life and politics. Everyone is able to find all the agreement, support, and groupthink needed, no matter what their position, or how loosely attached to reality.

Arguably, the algorithmically-driven society is responsible for some of the biggest changes in the social fabric of our time. In the UK, the Brexit Leave campaign was found to have weaponised algorithmic capabilities to help influence people’s attitudes and behaviors, with the networked effects of social media only adding to the power.

For Millennials, already well into our consumerist lives when this arrived, it can sometimes feel like we lacked the ability to really push back. We allowed ourselves to become ingrained with this way of life and to become dependent, ground down and too accepting.

But for Gen Z, something interesting has started to happen in recent years. We evolve culturally and mentally, more quickly than physiologically. Each next generation can take the cultural and social learnings of the previous generation, adapt, and thrive.

For Gen Z, there has been a real boom in algorithm-free living, in partially turning away from the loss of control and turning back to the analogue.

There has been a resurgence in vinyl purchases, rejecting the easy algorithmally-driven streaming platforms. In 2022, or the first time since 1987, vinyl albums outsold CDs.

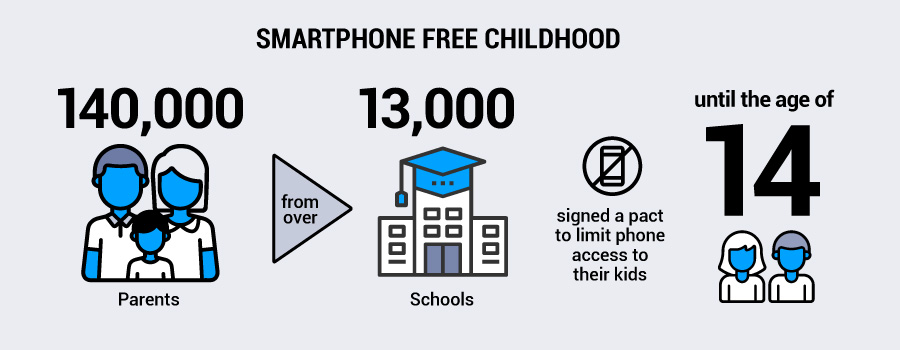

Dumb phones have also started to make a return, and the campaign group SmartPhone Free Childhood has made huge inroads in the public consciousness, leading to 140,000 parents from over 13,500 schools signing the pact to limit phone access to their kids until the age of 14.

IRL dating has also made a comeback, as people have gotten fed up seeing themselves, and those they wanted to date, being reduced to little more than attribute lists and a set of tangible and discreet features to tick off.

The pushback has been real, but evolution isn’t one-sided. The tech stack keeps changing, evolving, consuming data, developing pattern-matching and predictive capabilities, and creating the next battle ground.

Anthropomorphised algorithms

Which brings us to the present day and AI. Awareness, savviness, and concerns about The Algorithm are increasingly high. At the societal level there’s an understanding now that this is not just a benign tool that improves our lives, but rather a powerful force that shapes both individuals and society — and not always for the better.

In code we trust? Do we trust The Algorithm? In short, not so much. But something fascinating is now happening.

Algorithmic recommendations have gone from being the highlights, called-out feature to the embedded, invisible engine. Recessive, but all the more powerful for it.

AI interfaces have burst onto the scene over the last couple of years and have quickly become endemic. We use them for anything and everything, but the discursive and personable nature of the interactions means that we seem comfortable sharing far more with them than we would if we were consciously thinking about what we were doing.

There’s been a huge rise in AI as therapist, as friend, as confidante. In the absence of access to these relationships in the real world, as healthcare systems creak overloaded, as the loneliness epidemic rages on, AI is filling the gaps.

We’ve come full circle. We’ve gone back to sharing every last detail of our lives with the algorithm, but whereas in the early days we did it consciously and with excitement and anticipation, now we do it without really knowing. To paraphrase French poet Charles Baudelaire:

“The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing you it didn’t exist.”

We no longer see the algorithm or even think about it, just unwittingly hand over our deepest thoughts and needs to the machine. Even as we socially and culturally move to recognise its dangers and reject it, we’ve become distracted and have lost the ability to see it, falling under its spell to ever greater depths.

We’re now at a point where the underlying tension remains: we want all the benefits of being seen and understood without feeling watched and under attack.

Which perhaps takes us back to that moment in time, just before the turn of the century [1998 – Ed.], shortly after that Bezos interview, and the unwittingly prescient lyrics of one of the most enduring hits of the era, “Iris” by The Goo Goo Dolls:

“And I don’t want the world to see me

‘Cause I don’t think that they’d understand

When everything’s made to be broken

I just want you to know who I am“

What comes next is hard to know, but as our relationship with code — with the algorithm — continues to evolve, it will be fascinating to watch, whilst also knowing that we continue to be watched.