When handling customer data, understanding what kind of information you’re dealing with isn’t just good practice — it’s a legal requirement. Two terms that often create confusion are protected health information (PHI) and personally identifiable information (PII).

While there is overlap in some areas, the distinction matters significantly for privacy compliance, security protocols, and how you manage consent.

The PHI vs PII differences determine which regulations apply to your business, what security measures you need, and what penalties you might face for mishandling data. And knowing when you’re dealing with PHI and PII can impact your entire data strategy.

What is personally identifiable information (PII)?

- Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is any data that can identify an individual, such as name, Social Security number, email, or IP address.

- Protected Health Information (PHI) is a subset of PII that relates specifically to health data and is regulated under the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

- The main difference between PII vs PHI is scope: PII is broad, while PHI is limited to health-related data combined with personal identifiers.

- Compliance requirements vary: PHI is strictly regulated by HIPAA, while PII is governed by frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), and other state privacy laws.

- Mishandling PHI or PII can result in severe penalties, including HIPAA fines up to USD 50,000 per violation and GDPR penalties of up to EUR 20 million or 4 percent of global annual revenue.

- Organizations must implement strong security measures such as encryption, access controls, audit logging, and vendor risk management to protect both PHI and PII.

- Data minimization, de-identification, and retention policies reduce regulatory risk and help businesses manage sensitive information responsibly.

- Consent management platforms (CMPs) help organizations comply with overlapping regulations, streamline audit trails, and respect user choices across jurisdictions.

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), PII is: “any information about an individual maintained by an agency,” including:

- any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as name, Social Security number, date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, or biometric records

- any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.

In simpler terms, PII is any data that can identify a specific person, either on its own or when combined with other information. This definition is intentionally broad because the ways we can identify individuals keep expanding as technology evolves. Types of data categorized as PII vary by regulation.

PII falls into two main categories:

- Direct identifiers can identify someone on their own. A full name, Social Security number, passport number, or driver’s license number are all direct identifiers. If someone has access to just one of these pieces of information, they can pinpoint who a person is.

- Indirect identifiers need to be combined with other data to identify someone. So a date of birth, ZIP code, gender, or job title might not identify someone individually, but combine a few of these, and suddenly a person is distinguishable from everyone else. This is why seemingly harmless data can still qualify as PII.

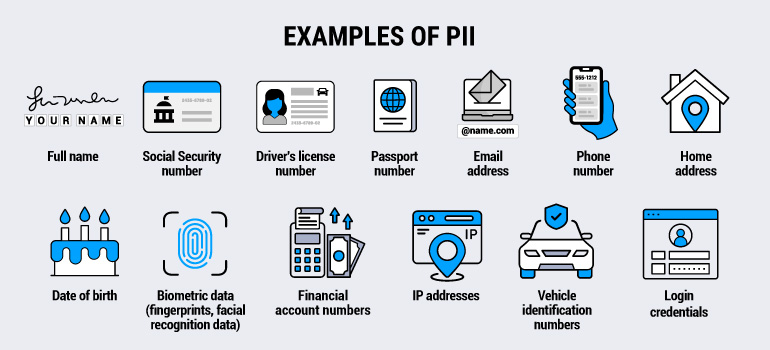

Examples of PII

The scope of what qualifies as PII can be extensive. Here are common examples:

- First and last name

- Social Security number (or other national identification number)

- Driver’s license number

- Passport number

- Email address

- Phone number

- Home address

- Date of birth

- Biometric data (fingerprints, iris scan, facial recognition data)

- Financial account numbers, including credit cards

- IP addresses

- Vehicle identification numbers and license plate numbers

- Account login credentials

When these data points are linked to an individual, they become PII. This means even seemingly anonymous data can transform into PII depending on the context and what other information it’s paired with.

What is protected health information (PHI)?

Protected health information is a specific subset of PII that relates to individuals’ health and healthcare. Under the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), PHI is individually identifiable health information that is created, received, maintained, or transmitted by HIPAA-covered entities and their business associates.

The key word is “health.” PHI doesn’t just include medical records. It covers any health information that can be linked to an individual. This includes information about one’s past, present, or future physical or mental health condition, healthcare services a person has received, or payment for those services.

HIPAA defines PHI using what’s commonly identified as the “18 identifiers” framework. When health information is combined with any of these 18 identifiers, it becomes PHI:

- Names

- Geographic subdivisions smaller than a state

- Dates directly related to an individual (birth dates, admission dates, discharge dates, death dates)

- Telephone numbers

- Fax numbers

- Email addresses

- Social Security numbers

- Medical record numbers

- Health plan beneficiary numbers

- Account numbers

- Certificate or license numbers

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers

- Device identifiers and serial numbers

- Web URLs

- IP addresses

- Biometric identifiers (fingerprints, iris scans, voiceprints)

- Full-face photographs

- Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code

What triggers PHI isn’t just the presence of health data or these identifiers alone. It’s the combination of both, plus context; specifically, whether the information is held or transmitted by a HIPAA-covered entity.

What is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)?

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), passed in 1996, is a federal law that protects patient health information (PHI) in the US. It applies to healthcare providers, insurers, clearinghouses, and their business associates.

HIPAA sets standards for how PHI is used, disclosed, and secured. For example, its Privacy Rule gives patients rights to access and correct their records, and the Breach Notification Rule ensures individuals are informed if their information is compromised.

Learn more about HIPAA, from who it protects to consent requirements.

Examples of PHI

PHI includes any health-related data that can be linked to an individual and is maintained by a covered entity. Therefore, lab results sent through a patient portal are a clear example.

The message contains your name, the doctor’s name, the test results, and your medical record number, all tied directly to your healthcare. Similarly, when an insurance company accesses your claim history, they are handling PHI, including billing records, diagnostic codes, and payment information linked to your member ID.

However, PHI is not limited to hospitals and insurers. A pharmacy notifying you that your prescription is ready is handling PHI, because the message connects your phone number with specific medication details.

Mental health apps provided through a healthcare provider can also generate PHI, such as mood tracking or therapy notes, because this information is health-related and maintained by a covered entity.

Even years after discharge, hospital admission records remain PHI, containing demographic information, treatment details, and payment records.

Key differences between PHI and PII

Understanding PHI vs PII comes down to three main distinctions: scope, regulation, and who handles the data. In short, PII is a broad category of personal data, while PHI is health-related information specifically protected under HIPAA.

Here are the key distinctions between PHI vs PII:

| PII | PHI | |

| Definition | Any data that identifies an individual | Health information linked to an individual |

| Scope | Broad: includes all personal identifiers | Narrow: limited to health-related data |

| Primary regulation | International and regional data privacy laws, like the GDPR or US state-level laws | HIPAA |

| Who must comply | Most organizations collecting personal data | HIPAA-covered entities and business associates |

| Examples | Name, email, SSN, address | Medical records, prescription data, health insurance claims |

| Security requirements | Varies by regulation | Strict HIPAA Security Rule requirements |

When PII becomes PHI

It’s worth noting that the same piece of information can be PHI in one context and PII in another. The shift from PII to PHI happens when health information gets linked to personal identifiers in a HIPAA-covered context.

For example, your fitness tracker collects heart rate data. If that data sits in your personal app disconnected from any healthcare provider, it’s just PII, or potentially not even that, if it’s not linked to identifying information.

But the moment you share that data with your doctor through a patient portal and it’s stored alongside your medical record number and name, it becomes PHI.

Similarly, if you mention in an online form that you have diabetes, that’s health-related PII. But when that information is collected by a health insurance company as part of your coverage application, it crosses into PHI territory because you’re now dealing with a HIPAA-covered entity.

This distinction matters because HIPAA compliance requirements are more demanding than general personally identifiable information HIPAA handling under most privacy laws. The consent requirements, security measures, and breach notification procedures all differ significantly.

PII compliance frameworks across industries

HIPAA and PII operate under different frameworks, but organizations handling personal data often need to navigate additional privacy regulations beyond both.

The following frameworks define what counts as PII, how it must be protected, and which rules apply depending on where data subjects reside or what type of data is collected.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation

The GDPR applies to personal data of individuals in the European Union. It includes health data as a special category requiring additional protections, but doesn’t use the PHI terminology.

Therefore, if you process data of EU residents, GDPR’s consent, data minimization, and security requirements apply regardless of whether you’re subject to HIPAA.

California’s Privacy Rights Act and other state privacy laws

The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) gives California residents rights over their personal information, including the right to know what’s collected, delete it, and opt out of its sale. The CPRA specifically identifies health data as sensitive personal information requiring opt-in consent before use.

Other states across the US have enacted similar laws, such as the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA), Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA), and more.

ISO 27701

ISO 27701 provides a framework for creating and maintaining a privacy information management system. It helps organizations demonstrate compliance with global privacy regulations, offering a structured approach to managing PII alongside PHI.

NIST SP 800-series

The NIST SP 800-series provides guidance on technical and administrative controls to safeguard PII. SP 800-122 focuses specifically on PII protection, while the broader NIST Privacy Framework helps organizations assess and manage privacy risks across systems.

For organizations handling both PHI and PII in healthcare contexts, the stricter standard typically applies. If HIPAA requires something that the CPRA doesn’t, you still need to meet HIPAA’s requirements for the PHI. Conversely, if a state law is more protective than HIPAA for certain data, that higher standard applies.

What happens if an organization fails to protect PHI and PII?

Mishandling personal data comes with serious consequences, but the stakes are particularly high when it involves PHI. HIPAA violations can lead to steep fines and are classified by severity:

- Unknowing violations carry USD 100–50,000 per incident

- Reasonable cause violations range from USD 1,000–50,000

- Willful neglect that’s corrected is up to USD 10,000–50,000

- Uncorrected willful neglect hits the USD 50,000 ceiling per violation

For PII, the rules and penalties vary depending on jurisdiction. For instance, under the GDPR penalties can reach €20 million or 4 percent of global annual revenue, whichever is higher.

In California, CCPA fines and penalties outline statutory damages of USD 107–USD 799 per consumer per incident, plus civil penalties from USD 2,663–USD 7,988 per violation.

Fines, however, are only part of the picture. Data breaches also erode trust, harm reputations, and trigger mandatory notifications to affected individuals. Companies may then face corrective action plans, ongoing regulatory monitoring, requirements to delete data or halt processing, and even criminal charges for egregious violations.

It’s also worth knowing that regulators are particularly vigilant about organizations that misclassify PHI as ordinary PII. Doing so signals a failure to apply appropriate HIPAA safeguards.

Just like selecting legitimate interest as your legal basis for data processing under the GDPR to save the work of obtaining valid consent doesn’t mean it’s legally justifiable, simply labeling health information as “just PII” does not exempt an organization from PHI requirements when handling data for or on behalf of covered entities.

How to secure PII and PHI

Understanding the rules around PHI vs PII is only one part of protecting sensitive information. The greater challenge is making sure data stays protected as it moves through your systems.

The steps below highlight key practices for keeping PII and PHI secure.

Conduct a data inventory and classification

Security starts with visibility. Organizations need to know what PII and PHI they hold, where it resides, how it flows between systems, and who has access to it. Once identified, classify data by sensitivity and document what is collected, why, how long it is retained, and any third-party sharing.

Implement access controls

The next step is controlling who can access this data. Apply the principle of least privilege so users only access what they need. Enforce multifactor authentication for sensitive systems, and regularly review and revoke unnecessary permissions. For PHI, HIPAA adds specific requirements, such as unique user IDs, automatic logoff, and encrypted login credentials.

Use encryption when needed

Even with tight access controls, data is still vulnerable if intercepted or exposed. Encryption provides a critical safeguard, both at rest and in transit from databases and backups to transmissions secured by TLS/SSL.

While HIPAA does not mandate encryption, it offers a safe harbor: Properly encrypted data generally avoids breach notification obligations if the keys remain uncompromised.

Maintain audit logs and monitoring

Encryption protects data in motion and at rest, but it is equally important to monitor how it is used. Audit logs provide visibility into who accessed sensitive information, when, and what actions they took.

HIPAA requires these logs for ePHI. Alerts for unusual activity can help detect breaches or insider threats, and retention of logs — six years under HIPAA — helps ensure compliance and accountability.

Design security into your architecture

Security should not be an afterthought. Security should be integrated into the architecture itself. Segment networks to isolate PHI and sensitive PII, apply firewalls and intrusion detection, and use secure configurations. Regular patching, penetration testing, and vulnerability assessments help close gaps before attackers can exploit them.

Manage vendor and third-party risks

Even the best internal security can be undermined by weak links in the supply chain. Any vendor handling PHI must sign a Business Associate Agreement, and those processing PII under the GDPR or the CPRA require a Data Processing Agreement (DPA).

Practice data minimization and retention management

Vendor oversight should be paired with discipline in data collection itself. Collect only what is necessary, and delete or anonymize it when it is no longer needed. Establish retention schedules that meet legal obligations while limiting unnecessary exposure.

For PHI, retention rules vary by state, while HIPAA compliance records must be preserved for six years.

Learn more about the data retention and deletion requirements of the GDPR.

De-identify data where appropriate

In some cases, organizations can reduce risk further by de-identifying data for research or analytics. HIPAA allows for two approaches: removing all 18 identifiers or obtaining expert determination that re-identification risk is minimal. Done correctly, this removes data from HIPAA scope; done poorly, it leaves individuals exposed.

Build robust consent management

Even when data is secured and minimized, individuals must have a say in how it is used or shared. HIPAA requires explicit authorization for uses beyond treatment, payment, and operations. And under the GDPR and the CCPA, organizations must provide clear notice, enable opt-outs, and respect rights such as access, correction, and deletion.

Consent management platforms (CMPs) make this easier by capturing preferences, automating opt-outs, and signaling proof of consent across systems and vendors.

Develop incident response and breach handling procedures

No security strategy is complete without preparation for incidents. Breaches can still occur, and a defined response plan helps detect, contain, and investigate them quickly.

However, notification rules vary. HIPAA requires disclosure within 60 days for large breaches, while the GDPR and state laws impose shorter timelines. Disclosure requirements can also vary by type and size of breach. Documenting each step supports compliance and builds trust through transparency.

Train your workforce regularly

Lastly, human error causes many data breaches, even if accidental. Provide ongoing training on HIPAA requirements, privacy practices, security protocols, and how to recognize phishing and social engineering attacks.

In fact, HIPAA requires privacy and security training for all workforce members with PHI access.

How can Usercentrics help you protect PII and PHI?

Organizations handling both PII and health data need consent systems that work across different regulatory requirements. Collecting valid consent for one regulation while respecting another creates operational friction, especially when the rules contradict or overlap.

Our consent management platform addresses PHI for marketing alongside broader PII compliance. You get documented audit trails, cross-platform preference management, and granular user controls that respect individual choices about data use.

Our platform integrates with your existing privacy infrastructure and adapts to the specific frameworks that apply to your data, such as GDPR for European users, CCPA for California residents, and HIPAA authorization for covered entities across the United States.

This means you can manage consent collection, storage, signaling, and proof of compliance from a single system instead of maintaining separate processes for each regulation. Our CMP also handles the complexity of overlapping requirements, so your team doesn’t have to map every edge case manually.