The United States does not have a comprehensive federal data privacy law that governs how businesses access or use individuals’ personal information. Instead, privacy protections and regulation are currently left to individual states. California led the way in 2020 with the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), later strengthened by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). As of January 2025, 20 states have passed similar laws. The variances in consumers’ rights, companies’ responsibilities, and other factors makes compliance challenging for businesses operating in multiple states.

The American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) sought to simplify privacy compliance by establishing a comprehensive federal privacy standard. The ADPPA emerged in June 2022 when Representative Frank Pallone introduced HR 8152 to the House of Representatives. The bill gained strong bipartisan support in the House Energy and Commerce Committee, passing with a 53-2 vote in July 2022. It also received amendments in December 2022. However, the bill did not progress any further.

As proposed, the ADPPA would have preempted most state-level privacy laws, replacing the current multi-state compliance burden with a single federal standard.

In this article, we’ll examine who the ADPPA would have applied to, its obligations for businesses, and the rights it would have granted US residents.

What is the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)?

The American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) was a proposed federal bill that would have set consistent rules for how organizations handle personal data across the United States. It aimed to protect individuals’ privacy with comprehensive safeguards while requiring organizations to meet strict standards for handling personal data.

Under the ADPPA, an individual is defined as “a natural person residing in the United States.” Organizations that collect, use, or share individuals’ personal data would have been responsible for protecting it, including measures to prevent unauthorized access or misuse. By balancing individual rights and business responsibilities, the ADPPA sought to create a clear and enforceable framework for privacy nationwide.

What data would have been protected under the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)?

The ADPPA aimed to protect the personal information of US residents, which it refers to as covered data. Covered data is broadly defined as “information that identifies or is linked, or reasonably linkable, alone or in combination with other information, to an individual or a device that identifies or is linked or reasonably linkable to an individual.” In other words, any data that would either identify or could be traced to a person or to a device that is linked to an individual. This includes data that may be derived from other information and unique persistent identifiers, such as those used to track devices or users across platforms.

The definition excludes:

- Deidentified data

- Employee data

- Publicly available information

- Inferences made exclusively from multiple separate sources of publicly available information, so long as they don’t reveal private or sensitive details about a specific person

Sensitive covered data under the ADPPA

The ADPPA, like other data protection regulations, would have required stronger safeguards for sensitive covered data that could harm individuals if it was misused or unlawfully accessed. The bill’s definition of sensitive covered data is extensive, going beyond many US state-level data privacy laws.

Protected categories of data include, among other things:

- Personal identifiers, including government-issued IDs like Social Security numbers and driver’s licenses, except when legally required for public display.

- Health information, including details about past, present, or future physical and mental health conditions, treatments, disabilities, and diagnoses.

- Financial data, such as account numbers, debit and credit card numbers, income, and balance information. The last four digits of payment cards are excluded.

- Private communications, such as emails, texts, calls, direct messages, voicemails, and their metadata. This does not apply if the device is employer-provided and individuals are given clear notice of monitoring.

- Behavioral data, including sexual behavior information when collected against reasonable expectations, video content selections, and online activity tracking across websites.

- Personal records, such as private calendars, address books, photos, and recordings, except on employer-provided devices with notice.

- Demographic details, including race, color, ethnicity, religion, and union membership.

- Biological identifiers, including biometric information and genetic information, precise location data, login credentials, and information about minors.

- Security credentials, login details or security or access codes for an account or device.

Who would the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) have applied to?

The ADPPA would have applied to a broad range of entities that handle covered data.

Covered entity under the ADPPA

A covered entity is “any entity or any person, other than an individual acting in a non-commercial context, that alone or jointly with others determines the purposes and means of collecting, processing, or transferring covered data.” This definition matches similar terms like “controller” in US state privacy laws and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). To qualify as a covered entity under the ADPPA, the organization would have had to be in one of three categories:

- Businesses regulated by the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act)

- Telecommunications carriers

- Nonprofits

Although the bill did not explicitly address international jurisdiction, its reach could have extended beyond US borders. Foreign companies would have needed to comply if they handle US residents’ data for commercial purposes and meet the FTC Act’s jurisdictional requirements, such as conducting business activities in the US or causing foreseeable injury within the US. This type of extraterritorial scope is common among a number of other international data privacy laws.

Service provider under the ADPPA

A service provider was defined as a person or entity that engages in either of the following:

- Collects, processes, or transfers covered data on behalf of a covered entity or government body

OR

- Receives covered data from or on behalf of a covered entity of government body

This role mirrors what other data protection laws call a processor, including most state privacy laws and the GDPR.

Large data holders under the ADPPA

Large data holders were not considered a third type of organization. Both covered entities and service providers could have qualified as large data holders if, in the most recent calendar year, they had gross annual revenues of USD 250 million or more, and collected, processed, or transferred:

- Covered data of more than 5,000,000 individuals or devices, excluding data used solely for payment processing

- Sensitive covered data from more than 200,000 individuals or devices

Large data holders would have faced additional requirements under the ADPPA.

Third-party collecting entity under the ADPPA

The ADPPA introduced the concept of a third-party collecting entity, which refers to a covered entity that primarily earns its revenue by processing or transferring personal data it did not collect directly from the individuals to whom the data relates. In other contexts, they are often referred to as data brokers.

However, the definition excluded certain activities and entities:

- A business would not be considered a third-party collecting entity if it processed employee data received from another company, but only for the purpose of providing benefits to those employees

- A service provider would also not be classified as a third-party collecting entity under this definition

An entity is considered to derive its principal source of revenue from data processing or transfer if, in the previous 12 months, either:

- More than 50 percent of its total revenue came from these activities

or

- The entity processed or transferred the data of more than 5 million individuals that it did not collect directly

Third-party collecting entities that process data from more than 5,000 individuals or devices in a calendar year would have had to register with the Federal Trade Commission by January 31 of the following year. Registration would require a fee of USD 100 and basic information about the organization, including its name, contact details, the types of data it handles, and a link to a website where individuals can exercise their privacy rights.

Exemptions under the ADPPA

While the ADPPA potentially would have had a wide reach, certain exemptions would have applied.

- Small businesses: Organizations with less than USD 41 million in annual revenue or those that process data for fewer than 50,000 individuals would be exempt from some provisions.

- Government entities: The ADDPA would not apply to government bodies or their service providers handling covered data. It also excluded congressionally designated nonprofits that support victims and families with issues involving missing and exploited children.

- Organizations subject to other federal laws: Organizations already complying with certain existing privacy laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), among others, were deemed compliant with similar ADPPA requirements for the specific data covered by those laws. However, they would have still been required to comply with Section 208 of the ADPPA, which contains provisions for data security and protection of covered data.

Definitions in the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)

Like other data protection laws, the ADPPA defined several terms that are important for businesses to know. While many — like “collect” or “process” — can be found in other regulations, there are also some that are unique to the ADPPA. We look at some of these key terms below.

Knowledge under the ADPPA

“Knowledge” refers to whether a business is aware that an individual is a minor. The level of awareness required depends on the type and size of the business.

- High-impact social media companies: These are large platforms that are primarily known for user-generated content. They would have to have at least USD 3 billion in annual revenue and 300 million monthly active users over 3 months in the preceding year. They would be considered to have knowledge if they were aware or should have been aware that a user was a minor. This is the strictest standard.

- Large data holders: These are organizations that have significant data operations but do not qualify as high-impact social media. They have knowledge if they knew or willfully ignored evidence that a user was a minor.

- Other covered entities or service providers: Those that do not fall into the above categories are required to have actual knowledge that the user is a minor.

Some states — like Minnesota and Nebraska — define “known child” but do not adjust the criteria for what counts as knowledge based on the size or revenue of the business handling the data. Instead, they apply the same standard to all companies, regardless of their scale.

Affirmative express consent under the GDPR

The ADPPA uses the term “affirmative express consent,” which refers to “an affirmative act by an individual that clearly communicates the individual’s freely given, specific, and unambiguous authorization” for a business to perform an action, such as collecting or using their personal data. Consent for data collection would have to be obtained after the covered entity provides clear information about how it will use the data.

Like the GDPR and other data privacy regulations, consent would have needed to be freely given, informed, specific, and unambiguous.

Under this definition, consent cannot be inferred from an individual’s inaction or continued use of a product or service. Additionally, covered entities cannot trick people into giving consent through misleading statements or manipulative design. This includes deceptive interfaces meant to confuse users or limit their choices.

Transfer under the ADPPA

Most data protection regulations include a definition for the sale of personal data or personal information. While the ADPPA did not define sale, it instead defined “transfer” as “to disclose, release, disseminate, make available, license, rent, or share covered data orally, in writing, electronically, or by any other means.”

What are consumers’ rights under the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)?

Under the ADPPA, consumers would have had the following rights regarding their personal data.

- Right of awareness: The Commission must publish and maintain a webpage describing the provisions, rights, obligations, and requirements of the ADPPA for individuals, covered entities, and service providers. This information must be:

- Published within 90 days of the law’s enactment

- Updated quarterly as needed

- Available in the ten most commonly used languages in the US

- Right to transparency: Covered entities must provide clear information about how consumer data is collected, used, and shared. This includes which third parties would receive their data and for what purposes.

- Right of access: Consumers can access their covered data (including data collected, processed, or transferred within the past 24 months), categories of third parties and service providers who received the data, and the purpose(s) for transferring the data.

- Right to correction: Consumers can correct any substantial inaccuracies or incomplete information in their covered data and instruct the covered entity to notify all third parties or service providers that have received the data.

- Right to deletion: Consumers can request that their covered data processed by the covered entity be deleted. They can also instruct the covered entity to notify all third parties or service providers that have received the data of the deletion request.

- Right to data portability: Consumers can request their personal data in a structured, machine-readable format that enables them to transfer it to another service or organization.

- Right to opt out: Consumers can opt out of the transfer of their personal data to third parties and its use for targeted advertising. Businesses are required to provide a clear and accessible mechanism for exercise of this right.

- Private right of action: Consumers can sue companies directly for certain violations of the act, with some limitations and procedural requirements. (California is the only state to provide this right as of early 2025.)

What are privacy requirements under the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)?

The ADPPA would have required organizations to meet certain obligations when handling individuals’ covered data. Here are the key privacy requirements under the bill.

Consent

Organizations must obtain clear, explicit consent through easily understood standalone disclosures. Consent requests must be accessible, available in all service languages, and give equal prominence to accept and decline options. Organizations must provide mechanisms to withdraw consent that are as simple as giving it.

Organizations must avoid using misleading statements or manipulative designs, and must obtain new consent for different data uses or significant privacy policy changes. While the ADPPA works alongside the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)’s parental consent requirements for children under 13, it adds its own protections for minors up to age 17.

Privacy policy

Organizations must maintain clear, accessible privacy policies that detail their data collection practices, transfer arrangements, retention periods, and rights granted to individuals. These policies must specify whether data goes to countries like China, Russia, Iran, or North Korea, which could present a security risk, and they must be available in all languages where services are offered. When making material changes, organizations must notify affected individuals in advance and give them a chance to opt out.

Data minimization

Organizations can only collect and process data that is reasonably necessary to provide requested services or for specific allowed purposes. These allowed purposes include activities like completing transactions, maintaining services, protecting against security threats, meeting legal obligations, and preventing harm or if there is a risk of death, among others. Collected data must also be proportionate to these activities.

Privacy by design

Privacy by design is a default requirement under the ADPPA. Organizations must implement reasonable privacy practices that consider the organization’s size, data sensitivity, available technology, and implementation costs. They must align with federal laws and regulations and regularly assess risks in their products and services, paying special attention to protecting minors’ privacy and implementing appropriate safeguards.

Data security

Organizations must establish, implement, and maintain appropriate security measures, including vulnerability assessments, preventive actions, employee training, and incident response plans. They must implement clear data disposal procedures and match their security measures to their data handling practices.

Privacy and data security officers

Organizations with more than 15 employees must appoint both a privacy officer and data security officer, who must be two distinct individuals. These officers are responsible for implementing privacy programs and maintaining ongoing ADPPA compliance.

Privacy impact assessments

Organizations — excluding large data holders and small businesses — must conduct regular privacy assessments that evaluate the benefits and risks of their data practices. These assessments must be documented and maintained, and consider factors like data sensitivity and potential privacy impacts.

Loyalty with respect to pricing

Organizations cannot discriminate against individuals who exercise their privacy rights. While they can adjust prices based on necessary financial information and offer voluntary loyalty programs, they cannot retaliate through changes in pricing or service quality, e.g. if an individual exercises their rights and requests their data or does not consent to certain data processing.

Special requirements for large data holders

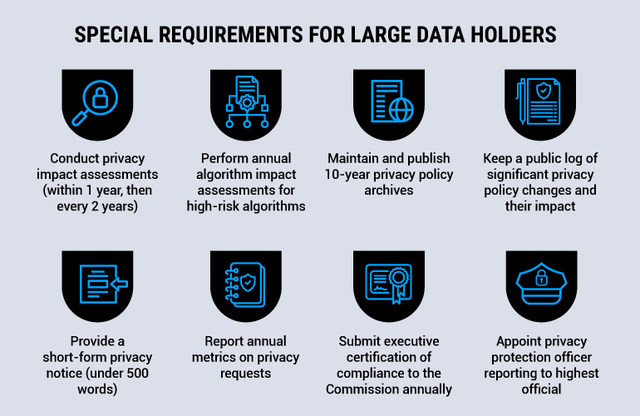

In addition to their general obligations, large data holders would have had unique responsibilities under the proposed law.

Privacy policy

Large data holders would have been required to maintain and publish 10-year archives of their privacy policies on their websites. They would need to keep a public log documenting significant privacy policy changes and their impact. Additionally, they would need to provide a short-form notice (under 500 words) highlighting unexpected practices and sensitive data handling.

Privacy and data security officers

At least one of the appointed officers would have been designated as a privacy protection officer who reports directly to the highest official at the organization. This officer, either directly or through supervised designees, would have been required to do the following:

- Establish processes to review and update privacy and security policies, practices, and procedures

- Conduct biennial comprehensive audits to ensure compliance with the proposed law and make them accessible to the Commission upon request

- Develop employee training programs about ADPPA compliance

- Maintain detailed records of all material privacy and security practices

- Serve as the point of contact for enforcement authorities

Privacy impact assessments

While all organizations other than small businesses would be required to conduct privacy impact assessments under the proposed law, large data holders would have had additional requirements.

- Timing: While other organizations must conduct assessments within one year of the ADPPA’s enactment, large data holders would have been required to do so within one year of either becoming a large data holder or the law’s enactment, whichever came first.

- Scope: Both must consider nature and volume of data and privacy risks, but large data holders would need to specifically assess “potential adverse consequences” in addition to “substantial privacy risks.”

- Approval: Large data holders’ assessments would need to be approved by their privacy protection officer, while other entities would have no specific approval requirement.

- Technology review: Large data holders would need to include reviews of security technologies (like blockchain and distributed ledger), this review would be optional for other entities.

- Documentation: While both would need to maintain written assessments until the next assessment, large data holders’ assessments would also need to be accessible to their privacy protection officer.

Metrics reporting

Large data holders would be required to compile and disclose annual metrics related to verified access, deletion, and opt-out requests. These metrics would need to be included in their privacy policy or published on their website.

Executive certification

An executive officer would have been required to annually certify to the FTC that the large data holder has internal controls and a reporting structure in place to achieve compliance with the proposed law.

Algorithm impact assessments

Large data holders using covered algorithms that could pose a consequential risk of harm would be required to conduct an annual impact assessment of these algorithms. This requirement would be in addition to privacy impact assessments and would need to begin no later than two years after the Act’s enactment.

American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) enforcement and penalties for noncompliance

The ADPPA would have established a multi-layered enforcement approach that set it apart from other US privacy laws.

- Federal Trade Commission: The FTC would serve as the primary enforcer, treating violations as unfair or deceptive practices under the Federal Trade Commission Act. The proposed law required the FTC to create a dedicated Bureau of Privacy for enforcement.

- State Attorneys General: State Attorneys General and State Privacy Authorities could bring civil actions on behalf of their residents if they believed violations had affected their state’s interest.

- California Privacy Protection Authority (CPPA): The CPPA, established under the California Privacy Rights Act, would have special enforcement authority. The CPPA could enforce the ADPPA in California in the same manner as it enforces California’s privacy laws.

Starting two years after the law would have taken effect, individuals would gain a private right of action, or the right to sue for violations. However, before filing a lawsuit, they would need to notify both the Commission and their state Attorney General.

The ADPPA itself did not establish specific penalties for violations. Instead, violations of the ADPPA or its regulations would be treated as violations of the Federal Trade Commission Act, subject to the same penalties, privileges, and immunities provided under that law.

The American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) compared to other data privacy regulations

As privacy regulations continue to evolve worldwide, it’s helpful to understand how the ADPPA would compare with other comprehensive data privacy laws.

The EU’s GDPR has set the global standard for data protection since 2018. In the US, the CCPA (as amended by the CPRA) established the first comprehensive state-level privacy law and has influenced subsequent state legislation. Below, we’ll look at how the ADPPA compares with these regulations.

The ADPPA vs the GDPR

There are many similarities between the proposed US federal privacy law and the EU’s data protection regulation. Both require organizations to implement privacy and security measures, provide individuals with rights over their personal data (including access, deletion, and correction), and mandate clear privacy policies that detail their data processing activities. Both also emphasize data minimization principles and purpose limitation.

However, there are also several important differences between the two.

| Aspect | ADPPA | GDPR |

|---|---|---|

| Territorial scope | Would have applied to individuals residing in the US. | Applies to EU residents and any organization processing their data, regardless of location. |

| Consent | Not a standalone legal basis; required only for specific activities like targeted advertising and processing sensitive data. | One of six legal bases for processing; can be a primary justification. |

| Government entities | Excluded federal, state, tribal, territorial and local government entities. | Applies to public bodies and authorities. |

| Privacy officers | Required “privacy and security officers” for covered entities with more than 15 employees, with stricter rules for large data holders. | Requires a Data Protection Officer (DPO) for public authorities or entities engaged in large-scale data processing. |

| Data transfers | No adequacy requirements; focus on transfers to specific countries (China, Russia, Iran, North Korea). | Detailed adequacy requirements and transfer mechanisms. |

| Children’s data | Extended protections to minors up to age 17. | Focuses on children under 16 (can be lowered to 13 by member states). |

| Penalties | Violations would have been treated as violations of the Federal Trade Commission Act. | Imposes fines up to 4% of annual global turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher. |

The ADPPA vs the CCPA/CPRA

There are many similarities between the proposed US federal privacy law and California’s existing privacy framework. Both include comprehensive transparency requirements, including privacy notices in multiple languages and accessibility for people with disabilities. They also share similar approaches to prohibiting manipulative design practices and requirements for regular security and privacy assessments.

However, there are also differences between the ADPPA and CCPA/CPRA.

| Aspect | ADPPA | CCPA/CPRA |

|---|---|---|

| Covered entities | Would have applied to organizations under jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission, including nonprofits and common carriers; excluded government agencies. | Applies only to for-profit businesses meeting any of these specific thresholds:gross annual revenue of over USD 26,625,000receive, buy, sell, or share personal information of 100,000 or more consumers or householdsearn more than half of their annual revenue from the sale of consumers’ personal information |

| Private right of action | Broader right to sue for various violations. | Limited to data breaches only. |

| Data minimization | Required data collection and processing to be limited to what is reasonably necessary and proportionate. | Similar requirement, but the CPRA allows broader processing for “compatible” purposes. |

| Algorithmic impact assessments | Required large data holders to conduct annual assessments focusing on algorithmic risks, bias, and discrimination. | Requires risk assessments weighing benefits and risks of data practices, with no explicit focus on bias. |

| Executive accountability | Required executive certification of compliance. | No executive certification requirement. |

| Enforcement | Would have been enforced by the Federal Trade Commission, State Attorney Generals, and the California Privacy Protection Authority (CPPA). | CPPA and local authorities within California. |

Consent management and the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA)

The ADPPA would have required organizations to obtain affirmative express consent for certain data processing activities through clear, conspicuous standalone disclosures. These consent requests would need to be easily understood, equally prominent for either accepting or declining, and available in all languages where services are offered. Organizations would also need to provide simple mechanisms for withdrawing consent that would be as easy to use as giving consent was initially. The bill also required organizations to honor opt-out requests for practices like targeted advertising and certain data transfers. These opt-out mechanisms would need to be accessible and easy to use, with clear instructions for exercising these rights.

Organizations would need to clearly disclose not only the types of data they collect but also the parties with whom this information is shared. Consumers would also need to be informed about their data rights and how to act on them, such as opting out of processing, through straightforward explanations and guidance.

To support transparency, organizations would also be required to maintain privacy pages that are regularly updated to reflect their data collection, use, and sharing practices. These pages would help provide consumers with access to the latest information about how their data is handled. Additionally, organizations would have been able to use banners or buttons on websites and apps to inform consumers about data collection and provide them with an option to opt out.

Though the ADPPA was not enacted, the US does have an increasing number of state-level data privacy laws. A consent management platform (CMP) like the Usercentrics CMP for website consent management or app consent management can help organizations streamline compliance with the many existing privacy laws in the US and beyond. The CMP securely maintains records of consent, automates opt-out processes, and enables consistent application of privacy preferences across an organization’s digital properties. It also helps to automate the detection and blocking of cookies and other tracking technologies that are in use on websites and apps.

Usercentrics does not provide legal advice, and information is provided for educational purposes only. We always recommend engaging qualified legal counsel or privacy specialists regarding data privacy and protection issues and operations.