In 2025, privacy isn’t just a legal requirement — it’s a brand imperative.

“The State of Digital Trust in 2025”, a new global study commissioned by Usercentrics, reveals a major turning point: consumers are changing the way they consider data collection and sharing in the digital world. They’re more privacy-aware, more trust-conscious, and more willing to act when brands fall short.

Consumers’ concerns and demands for more control are growing

In today’s complex digital landscape, people aren’t rejecting data-sharing. They’re questioning, hesitating, and looking for proof that brands will use their data responsibly. This isn’t about saying no to personalization or innovation. It’s about demanding control, clarity, and accountability.

For marketers, this shift is a powerful opportunity. Privacy-led strategies aren’t just about legal compliance; they’re a competitive advantage. Privacy-Led Marketing is a strategy that helps brands meet rising expectations, stand out in crowded markets, and build lasting loyalty at a time when trust is the ultimate differentiator.

How marketers can lead with transparency and consent

The report lays out a clear roadmap for marketers who are ready to lead with transparency. Here are four of the key insights.

1. Consumers feel like the product — and they’re pushing back

People are increasingly aware of how their data fuels the digital economy, and many are growing comfortable with that data being used — under certain conditions.

- 62% feel they’ve become the product

- 59% are uneasy about their data training AI

- Nearly half trust AI less than humans with personal data

This signals a new baseline: trust must be earned, not assumed. Transparency and respectful data practices aren’t optional — they’re expected.

2. Consent has evolved from a legal checkbox to first brand impression

Consumers are thinking before they click. The cookie banner has become a moment of truth when it comes to trust.

- 42% read cookie banners “always” or “often”

- 46% accept cookies less often than they did three years ago

- 36% have adjusted their privacy settings

Consent interactions are now a frontline brand experience. A clear, respectful approach builds trust. A vague or manipulative one damages it from the very first click.

3. Trust is conditional and not evenly distributed

People are becoming more selective about which brands they trust, and the bar is high.

- 44% want transparency about how data is used

- 43% expect strong security guarantees

- 41% want real control over what’s shared

Highly regulated sectors like finance and the public sector enjoy higher levels of trust. Meanwhile, industries like tech, retail, and automotive are lagging. In today’s trust economy, clarity and evidence are the new currency.

4. The privacy knowledge gap is real — but brands can lead

Consumers care about privacy, but many don’t fully understand how their data is collected or used.

- 77% don’t fully understand how their data is handled

- 40% believe they have rights, but don’t know what they are

- Only 47% trust regulators to hold Big Tech accountable

This creates a huge opportunity. Brands that simplify, educate, and empower can become trusted allies, and turn confusion into confidence, hesitation into loyalty.

Discover how leading marketers are turning transparency into a competitive edge, and why privacy is the new foundation of brand trust.

About the research/methodology

This report is based on a survey by Sapio Research, commissioned by Usercentrics, of 10,000 consumers who frequently use the internet across Europe (the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands) and the USA. Interviews were conducted in May 2025. The research aimed to uncover the true state of data privacy and digital trust today, and provide businesses with guidance on how to develop their consumer data consent strategy.

As AI hype accelerates and Big Tech’s influence expands, consumers are demanding more than just convenience, they’re demanding accountability. In 2025, trust has evolved from a compliance checkbox into a central consumer concern that brands need to take into account.

For marketers, privacy can no longer be an afterthought. It must be embedded into marketing strategy. The brands leading today are those creating meaningful experiences with their customers by embedding privacy into the core of the customer journey.

This shift marks a pivotal moment for marketers. Consumers aren’t rejecting data-sharing, they’re taking an active role in deciding who gets access to their data and why.

Those who adopt a privacy-first mindset won’t just meet rising expectations, they’ll earn a lasting competitive advantage by establishing close and trusting relationships with consumers. Those who don’t will lose relevance — and revenue — as consumers choose brands that respect their data.

| Chapter 1: The algorithm effect: How AI turned data into a trust issue | Chapter 2: Consent clicks: Privacy choices = marketing moments | Chapter 3: Not all brands are trusted equally | Chapter 4: From privacy pressure to brand power |

| People know their data has value and feel uneasy when they’re kept in the dark or feel out of control with how it’s used. AI hype has made data use even more visible. | Consumers are actively engaging with consent banners. “Accept all” is no longer a reflex, it’s a definite decision. | Consumers don’t trust all brands equally, and nearly half say being clear about how their data is used is the single most important factor in earning their trust. | Consumers are signaling that they care about privacy, but they’re still unsure how it works. |

| 62% of people feel they have become the product, and 59% are uncomfortable with their data being used to train AI. | 42% read cookie banners “always” or “often”, while 46% click “accept all” cookies less often than they did three years ago. | 44% say transparency about data use is the number one driver for trusting a brand. | 77% of global consumers don’t fully understand how their data is being collected and used by brands. |

For brands, Privacy-Led Marketing is about more than ticking legal checkboxes or meeting regulatory standards. It’s a growth imperative, an opportunity to stand out, build deeper loyalty, and grow in a market where trust is the ultimate differentiator.

About this research: This report is based on a survey by Sapio Research, commissioned by Usercentrics, of 10,000 consumers who frequently use the internet across Europe (the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands) and the USA. Interviews were conducted in May 2025. The research aimed to uncover the true state of data privacy and digital trust today, and provide businesses with guidance on how to develop their consumer data consent strategy.

Chapter 1: The algorithm effect – How AI turned data into a trust issue

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the relationship between people and their data, and not always for the better. As these systems become more advanced, their opacity deepens concerns about how and why users’ data is used.

AI systems are now baked into everyday life: powering recommendations, predicting preferences, automating decisions, and, with that, sometimes even influencing how we perceive reality.

But as the presence of AI grows, so too does public discomfort with how these systems are trained and deployed — especially when personal data is involved.

These aren’t just statistics, they’re signals. AI is triggering a shift in the public’s understanding of privacy, and with it, a demand for new kinds of trust.

The discomfort around personal data being to train AI models is real; and it creates a trust gap that brands must prioritize closing. If ignored, they risk reputational damage and losing user loyalty.

What used to be an abstract concern — “my data is out there” — has become deeply personal. Consumers are starting to ask sharper, more informed questions:

- What is my data being used for?

- Who is profiting from it?

- What role does it play in training machines that affect me?

Consumers no longer want vague promises of “data protection.” They want proof that brands know what data they collect, how it’s being used, and most importantly — why.

When people feel their data is being fed into opaque algorithms that serve corporate goals rather than human needs, trust erodes. This shift raises the bar for brands to not only ask for data, but justify its use in ways that feel fair and transparent.

We’ve reached a turning point

In 2025, trust isn’t built with fine print. It’s built with transparent systems, explainable models, and ethical data practices. People want to see how decisions are made, what they’re based on, and how they can opt out if they choose. They’re looking for brands that don’t just ask for consent, but actually mean it.

This is the foundation of Privacy-Led Marketing, a strategy built not just on privacy compliance, but on clarity. Brands that are willing to engage in the AI and data conversation (rather than avoid it) are positioned to stand apart.

Tip for Marketers: AI anxiety is real and growing. Don’t ignore it.

Instead of hiding behind algorithms, humanize them. Explain how your AI systems work: show people what data is used, and why. Give them real choices. Trust isn’t a feature; it’s a feeling. And you have to earn it.

Chapter 2: Consent clicks – Privacy choices = marketing moments

Consumers are moving from awareness to action, becoming more intentional in how they manage their data. They’re reading cookie banners, rejecting vague terms, and actively adjusting their settings.

What was once a passive click is now a conscious choice, and that shift is reshaping how people engage with brands from the very first interaction.

Consumers are more privacy aware and are acting on it. 42 percent read cookie banners “always” or “often”, signalling growing consumer intent to participate in their own data governance, a shift that redefines consent as an ongoing dialogue, not a one-time ask.

Nearly half of consumers (46 percent) click “accept all” for use of cookies less often than they did three years ago, according to the survey. This is more pronounced in mainland Europe, with Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany leading the way in this trend.

This behavior signals declining blind trust. Brands relying on dark patterns or vague messaging may find engagement falling — not due to apathy, but active resistance.

A further 36 percent of consumers globally have actively adjusted their privacy settings on websites or apps, and the same number have stopped using a website or deleted an app due to privacy concerns.

The data also reveals that those who are more privacy-informed are even more likely to modify cookies and take control over their data.

Importantly, most consumers (65 percent) are still happy for brands to collect their data, but they are taking real steps to control their data, rather than blindly accepting all. People aren’t rejecting data collection altogether; they’re rejecting vague terms, overly complex choices, and unclear value.

In short, privacy has taken a bigger role in the consumer decision journey. That first consent banner isn’t a compliance formality, it’s a brand moment. Done right, it is an opportunity to demonstrate restraint while building respect and trust. Done poorly, it creates mistrust from the first click and also depletes your consented data in the process.

Marketers have a powerful opportunity to lead the privacy conversation, guiding user-first experiences that convert consent into connection, and privacy into performance.

By rethinking consent UX and messaging — from dark patterns to clear value propositions — brands can turn a once-maligned legal step into a moment that builds trust, credibility, and even conversion.

This shift also reframes privacy from a blocker to a growth lever. It’s not just about minimizing opt outs. It’s about maximizing opt-ins and a chance to prove that you respect your customers and users and their preferences.

Tip for Marketers: Design your consent banner like it’s a landing page. See it as your first handshake with customers. Turn consent into a contextual brand moment.

Ask for consent only when relevant, at checkout, for instance, and explain the benefit (e.g. ”so we can personalize your cart”.) That clarity builds trust and strengthens brand connection.

Chapter 3: Not all brands are trusted equally

Data privacy and security are playing an increasingly crucial role in building trust. Consumers are clear about what they expect from brands in exchange for their data. Meeting these expectations is no longer a bonus. It’s a baseline for earning attention, engagement, and repeat interaction.

What would improve your trust in how a brand uses your data?

- Transparency about data use (44%)

- Strong security guarantees (43%)

- Ability to limit or control data sharing (41%)

Trust isn’t freely given any more — it’s conditional. Brand promises aren’t taken at face value. Consumers want evidence: proof that their data is being handled responsibly and securely, and that they’re being given real choices and control.

Consumers also don’t trust all brands equally, and the differences in where they place trust might be surprising.

External factors play a critical role in establishing that trust. Industries that are more heavily regulated, like finance and the public sector, tend to enjoy higher levels of trust when it comes to data collection and usage.

By contrast, technology and social media companies have been increasingly scrutinized by regulators, media, and the public, so it’s unsurprising that these industries have lower levels of trust among consumers.

That said, highly customer-centric sectors like retail might be surprised to find they rank so low, while among Gen Z, 39 percent rank social media platforms as trustworthy.

Similarly, trust is no longer strongly tied to geography. Consumers are nearly as cautious about sharing data with businesses from the USA (73 percent) as they are with those from China (77 percent).

Other European countries, traditionally viewed as more trusting, rank only an average 10 percentage points lower in terms of consumer caution, highlighting that trust is relative, not guaranteed.

Know your audience

The good news? Regardless of what sector or geography your brand is in, consumers are clear about what they want and how brands should engage with them before collecting and using personal data.

Brands that communicate clearly and openly from the outset about how they handle data won’t just achieve compliance with regulations, they’ll build credibility and deepen customer relationships and engagement. And in a competitive landscape, trust becomes your most powerful differentiator.

Tip for Marketers: Understand that security and data transparency build brand trust more than geography or industry.

Chapter 4: From privacy pressure to brand power

Consumers are clearly signaling that privacy management matters to them, but many still don’t fully understand how it works. This creates a powerful opportunity for forward-thinking brands: those who lead with education and transparency will build trust and gain a meaningful advantage.

Consumers want to feel in control of their data, but many still don’t fully understand how it’s collected or used.

There’s momentum: consumers are clicking “accept all” less often, adjusting their settings, and signaling that they care more and more about who has their data and what is being done with it. But a knowledge gap remains.

That confusion creates a wedge between your brand and your audience. When clarity is missing, so is confidence, and with it, the willingness to share data.

This is where brands can step in — not as enforcers, but as enablers. While trust in governments and regulators is uncertain, brands that offer transparency and guidance can become the trusted voice consumers turn to, because in the digital world trust is the foundation of lasting relationships.

Privacy literate behavior is growing, but there’s still a need for education. In today’s complex digital landscape, clarity and reassurance are rare, but valuable.

Move beyond compliance to customer advocacy

The smartest brands won’t wait for regulation to catch up. Waiting means losing ground to competitors who move faster and earn trust sooner. Instead, they’ll act as privacy champions:

- Collection: Setting up a consent management platform CMP correctly and supporting contextual consent

- Activation: Using consented data responsibly to deliver trustworthy experiences

- Measurement: Making use of Server-Side Tagging (SST) to control data flows responsibly

And most importantly, communicating these practices clearly and positively.

This isn’t just about giving people choices. It’s about making those choices meaningful and easy to understand. When brands take the lead, they not only build trust. They create differentiation, loyalty, and long-term growth.

Tip for Marketers: Pivot to building a modern, consent-based journey, one that considers how you collect, activate, and measure consented data at every touchpoint.

Chapter 5: Action plan — a marketer’s guide to privacy-led growth

The digital economy runs on data, but the rules of engagement are being rewritten. A EUR 600 billion ecosystem built on passive tracking and third-party data is being reshaped by global regulation, heightened consumer awareness, and the erosion of traditional identifiers.

Today, consumers don’t share data by default when they have a choice. As the research in this report shows, they’re opting out, speaking up, and making intentional privacy choices.

Meanwhile, marketers — still the biggest users of personal data — are facing a new reality: privacy isn’t just a legal obligation; it’s a brand differentiator, and a strategic necessity.

From obligation to opportunity: The privacy-led shift

Privacy-Led Marketing is how modern brands turn these pressures into performance. It’s a mindset shift from compliance checklists to competitive strategy. It doesn’t slow growth: it unlocks it.

This approach goes beyond permission and policy. It’s about embedding trust at every touchpoint to fuel better data, richer relationships, and sustained growth. Privacy becomes a driver of marketing precision, not a barrier to it.

At its core, Privacy-Led Marketing is about activating the full value of data — consented and responsibly modeled — across the lifecycle, from collection and activation to measurement and optimization.

These aren’t just more respectful experiences — they’re more effective ones. When done right, they reduce friction, increase confidence, and convert attention into loyalty.

What Privacy-Led Marketing unlocks

Brands that embed privacy into their customer experience gain far more than compliance:

- Trust as a growth lever: Transparency builds emotional equity, not just legal cover

- First-party strength: Direct customer relationships reduce third-party dependency

- Performance control: Privacy-respecting data strategies increase agility and long-term marketing resilience

Privacy-Led Marketing turns rising expectations into brand elevation. It’s a way to demonstrate your values — not just declare them — and convert trust into tangible business results.

How to start: The Privacy-Led Marketing checklist

These principles build on the research and insights in this report. Apply them across your marketing journey.

1. Lead with clarity in a world of AI and algorithms

Why it matters: AI and Big Tech have made consumers more aware — and more wary — of how their data is used. Marketers must lead with clarity and respect.

- Communicate clearly. Don’t just collect data, explain how it’s used. Transparency builds trust.

- Put value on the table. Make sure users understand what they get in return for sharing their data.

- Earn more than just consent. Earn attention and understanding. Use privacy as a way to show your brand’s ethics, not just your legal compliance. Because collecting data isn’t only about permission, it’s about understanding your customers, their needs, and what matters to them.

2. Design privacy as a brand touchpoint

Why it matters: Design your consent banner like it’s a landing page. See it as your first handshake with customers.

- Give consent the UX treatment. Design banners like landing pages: clear, helpful, and branded.

- Turn clicks into conversations. Make privacy interactive and engaging, not passive or hidden.

- Respect the pause. When users stop to consider consent, reward their attention with clarity and control.

3. Use transparency to differentiate your brand

Why it matters: Consumers trust what they can see, not just where you’re from or what industry you’re in.

- Deliver on expectations. Lead with transparency, show your security practices, and make control real.

- Don’t rely on reputation. Even traditionally trusted sectors are being re-evaluated. Trust must be earned at every touchpoint.

- Let transparency drive differentiation. Use your data practices as a brand advantage, not a backend process.

4. Make privacy understandable — and valuable

Why it matters: Consumers want to act on privacy, but many don’t know how. Marketers can bridge the gap.

- Educate without overwhelming. Use plain language, helpful visuals, and clean UX to guide users.

- Make privacy accessible. Well-designed banners and preference centers are brand tools, not legal obligations.

- Champion understanding. Be the brand that helps people feel confident in their choices, not confused by them.

About Usercentrics

Usercentrics is a global market leader in solutions for data privacy and activation of consented data. Our technology solutions enable customers to manage user consent for websites, apps and CTV. Helping clients achieve privacy compliance, Usercentrics is active in 195 countries on more than 2.3 million websites and apps. We have over 5,400 partners and handle more than 7 billion monthly user consents. Learn more on usercentrics.com.

In the United States, California has led the way in regulating data privacy at the state level. The CCPA was the first comprehensive modern state-level privacy law in the US and has been influential on subsequent legislation drafted in other states.

It would be logical to think that the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA) is another recent regulation. A framework designed to help manage the ever-increasing prevalence of technology in our lives and in business, along with the vast amounts of data we create and that businesses want to access. But CIPA predates the digital era by decades.

The original goal of CIPA was to protect the privacy of California residents in connection with phone calls, and was enacted long before ecommerce or the existence of social media platforms.

We look at what CIPA covers and how it’s applicable today, what rights consumers have, what obligations it places on businesses, the scope of penalties for violations, and more.

What is the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA)?

The California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA) was passed in 1967 and has been amended several times in the succeeding decades. It’s meant to protect the privacy of California residents’ confidential communications.

Even before the internet era, people had growing concerns about technology use in communications and the increasing ease of wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping without their knowledge or consent.

CIPA regulates when and how conversations and communications can be recorded. This applies to both contacting consumers and recording confidential communications, and arguably covers not just wiretapping, but potentially digital marketing activities.

Consent is a major requirement of CIPA, — even more than in the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

However, a lot has changed since 1967. Since CIPA is still on the books, it must still be relevant, right? In addition to protecting phone conversations, for example, there is ongoing litigation attempting to expand the scope of the regulation to communication via websites, apps, and tracking and recording technologies used on them.

Key requirements and prohibitions of CIPA

Enacting CIPA was meant to set a standard of establishing strong privacy rights around communications for California residents. The key goals of the regulation were:

- Detering unauthorized surveillance and recording/data collection

- Establishing clear consent requirements

- Creating accountability for violators

- Protecting privacy rights

- Adapting privacy protections (as technologies evolve)

Here are notable Sections in CIPA with regards to data privacy and individuals’ rights.

- Section 631: Sometimes called the “anti-wiretapping” rule, it prohibits unauthorized interception or recording of any communication (wired or electronic, which can include video conferencing) unless all parties involved give consent (with exceptions.)

- Section 632: Focuses on the recording of confidential conversations, defined as when participants have a reasonable expectation of privacy. Recording such conversations is prohibited unless all parties give consent (with exceptions.)

- Section 632.5 was added in 1985 to include cellular phones and conversations

- Section 632.6 was added in 1992 to include cordless phones and conversations

- Section 632.01 was added in 2017, criminalizing recording and intentional disclosure or distribution of confidential communications involving healthcare providers without consent

- Section 637.2: Allows individuals whose privacy rights have been violated to sue violators for damages up to USD 5,000 or three times an individual’s actual damages, whichever is more.

- Section 638.51: Prohibits the installation or use of a pen register or trap and trace device without consent or a court order. Dozens of recent lawsuits allege that this includes cookies and other tracking technologies used on websites.

CIPA definitions

Technology has advanced significantly since CIPA was passed. Definitions included in the regulation have been argued to encompass today’s devices, platforms, and types of communication.

Person: An individual, business association, partnership, limited partnership, corporation, limited liability company, or other legal entity.

Confidential communications: Communications made in circumstances that reasonably indicate the parties desire it to be confined to them, excluding communications made in circumstances where parties may reasonably expect that the communication may be overheard or recorded.

Wire communication: Any aural transfer made in whole or in part through the use of facilities for the transmission of communications by the aid of wire, cable, or other like connection between the point of origin and the point of reception (including the use of a like connection in a switching station), furnished or operated by any person engaged in providing or operating these facilities for the transmission of communications.

Electronic communication: Any transfer of signs, signals, writings, images, sounds, data, or intelligence of any nature in whole or in part by a wire, radio, electromagnetic, photoelectric, or photo-optical system. Does not include any of the following:

- Any wire communication

- Any communication made through a tone-only paging device

- Any communication from a tracking device

- Electronic funds transfer information stored by a financial institution in a communications system used for the electronic storage and transfer of funds

Pen register: A device or process that records or decodes dialing, routing, addressing, or signaling information transmitted by an instrument or facility from which a wire or electronic communication is transmitted, but not the contents of a communication.

Trap and trace device: A device or process that captures the incoming electronic or other impulses that identify the originating number or other dialing, routing, addressing, or signaling information reasonably likely to identify the source of a wire or electronic communication, but not the contents of a communication. This can include website tracking technologies.

Tracking device: means an electronic or mechanical device that permits the tracking of the movement of a person or object.

Who must comply with the CIPA?

CIPA can apply to companies and potentially covers a variety of customer or prospect interactions. However, it can apply to a broad range of entities if they intercept, intentionally overhear, or record private communications without all parties’ consent.

This includes individuals, employers, businesses, technology providers, and government entities when intercepting, monitoring, recording, or manufacturing or operating relevant equipment.

When does CIPA or CCPA compliance apply?

It can be tricky to understand when CIPA or the CCPA/CPRA applies, especially with the speed of change and introduction of new technologies. Even though the CCPA/CPRA passed decades after CIPA, and according to the text of the California Civil Code (§ 1798.175), was intended to further the constitutional right of privacy and to supplement existing laws relating to consumers’ personal information.

For example, under the CCPA/CPRA, collecting personal information on websites and processing it is legal in most cases without prior consent. Companies just have to give individuals the ability to opt out of the sharing or sale of their data, or its use for targeted advertising or profiling.

At the same time, under CIPA, individuals’ consent may need to be obtained before companies can communicate with them or record interactions, e.g. for marketing emails or customer support calls.

It can potentially be even more complicated with tracking on websites or apps. Technologies like cookies collect personal data, which is legal under CCPA without consent in most cases.

But such technologies that track individuals on or across websites without prior consent could arguably violate CIPA.

With online chat, whether between a customer and a human representative or a chatbot or other virtual assistant, companies can collect personal data from individuals during such interactions, but if the interactions are recorded companies need to disclose this.

Whether companies also need to notify customers about or obtain explicit consent to process the data from recorded interactions is a question currently being hashed out in the courts and the California state legislature. The outcomes of legislative action, lawsuits, and case law will continue to refine the answers to these questions.

However, to simplify operations and privacy compliance, it’s strongly recommended for companies to consult with qualified legal counsel and to adopt privacy best practices, including Privacy-Led Marketing strategies.

Disclosing monitoring and recording and requesting consent even when it’s not strictly necessary can show people that you respect their privacy and data. It also helps future-proof marketing activities and other operations over time, saving resources as technologies and regulations evolve.

Exceptions to the California Invasion of Privacy Act

While, as the law is currently written, most companies interacting with California residents for commercial purposes and engaging in various kinds of monitoring and recording will need to comply with CIPA, there are exceptions:

- Public utilities, including phone companies that provide communications facilities and services in connection with certain daily operations

- Telephone communication providers or systems used for communication exclusively within a state, county, city and county, or city correctional facility

- Conversations not considered confidential, including those taking place in a public setting

- Conversations or interactions where all parties involved have consented to recording

- Law enforcement officers can intercept and record communications if they have obtained a warrant or other judicial approval

- Emergency services can record conversations to obtain evidence of certain crimes

- Hearing aids and similar devices used by people with hearing impairments

Proposed amendment affecting CIPA applicability

On March 25, 2025, SB-690 was proposed in the California Senate, and passed there unanimously on June 3, 2025. The bill is with the state Assembly for consideration.

This bill proposes to amend CIPA to close an existing loophole, specifically so that the regulation would not apply to uses, devices, and processes for “commercial purposes” or subject to a consumer’s opt-out rights.

If passed, this bill would help clarify opt-in/opt-out standards and requirements for use of online marketing tools in California — and the US — and could potentially end a large wave of CIPA litigation in the country.

If passed in its initially proposed form, the bill would have applied retroactively to any case pending as of January 1, 2026. However, on May 30, 2025, in a significant amendment to the bill, the retroactivity provision was removed.

Since SB-690 was introduced there has been an acceleration of cases filed, and an additional increase in case filings is expected with the removal of the retroactivity provision, as the law would not affect ongoing litigation if passed.

What are consumers’ rights under the California Invasion of Privacy Act?

Under CIPA consumers have four major types of rights. Some of these will look familiar compared with other data privacy regulations and their requirements.

Right to notification

Businesses that record interactions with customers, e.g. phone calls, must provide individuals with clear notification at the start of the call and enable the individual to consent or end the call.

The notification must be provided in clear, understandable language before any substantive communication occurs, with an obvious opportunity to opt out or disconnect from the call.

Right to consent

The consent of all parties involved in a private conversation is required before it can be legally recorded or monitored, aka “all-party consent.” Consent is defined as explicit — verbal or written agreement to be monitored or recorded — or implied — a clear indication or continued participation after notification.

This notification must be provided to customers with every interaction, even if they have contacted the company before and heard it.

Right to privacy in conversations

Individuals have the right to privacy in their conversations and in electronic communications where confidentiality is a reasonable expectation. This includes places and communications like:

- Private homes

- Offices or workplaces

- Landline or mobile telephone conversations

- Text messages, direct messages, and other private electronic communications

- Other settings where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy

Right to legal remedies

Individuals whose rights under CIPA have been violated have more options than under many other privacy laws:

- Seek injunctive relief to stop ongoing violations

- Seek damages by filing a civil lawsuit (private right of action)

- Report violations for possible criminal prosecution of the violator

The penalties per violation can add up quickly. Also of note is that the CCPA, by contrast, only enables California residents to sue in the event of a data breach.

There have been a number of cases where CIPA has been used to enable victims of privacy violations that were not data breaches to seek redress. For example, in cases of being recorded or having information from interactions used without their knowledge or consent.

Individuals suing for damages must establish that the communication that occurred was confidential and they had a reasonable expectation of privacy, as well as that the communication was intercepted or recorded without proper consent.

What are organizations required to do for CIPA compliance?

Best practices to comply with CIPA will look familiar to those who already work to achieve and maintain data privacy compliance in California.

The good news is that if your company already complies with regulations like the CCPA or GDPR, you’re potentially already implementing these recommendations.

Provide clear notifications and consent management options

Determine which of your company’s operations require prior consent under CIPA. For example, do you need to inform customers at the beginning of customer support phone calls about recording and enable them to opt out?

Where legal requirements are still being determined, adopting best practices can reduce legal risks. For example, if your website uses a chatbot, provide a clear notification when the function is initiated about potential recording or use of the data from the interaction, and enable opt-out.

In addition to helping protect your company from regulatory violations, providing this information along with clear choices helps build trust with your customers and website visitors.

Implement and maintain a clear privacy policy

Your company should already have a clear, comprehensive privacy policy, especially if you’re complying with regulations like the CCPA or GDPR. Ensure that you provide notification about monitoring or recording on your website or in other customer interactions.

Be clear about what information may be recorded, how it may be used, and who may have access to it. Explain consent options and how to contact your company for additional information.

As the law and technologies businesses use evolve, ensure your privacy policy is kept up to date to reflect your operations and legal obligations. Automated consent management tools can help with this maintenance.

Provide ongoing privacy and consent management training

Include CIPA requirements in your security and data privacy training for staff. Customize the training for specific roles, e.g. the customer support team. Repeat the training on a regular basis to onboard new staff and to keep the knowledge fresh and ensure new operations or technologies are covered.

Ensure that staff know about the company’s monitoring and recording practices, via which technologies, and can provide information about how collected data is used and how to ensure opt-out requests are respected.

Use a comprehensive consent management solution

Depending on your operations, data collection, and relevant regulations, there are different tools to help you manage consent requirements. Customer relationship management (CRM) systems often have tools to manage consent for recorded communications.

Consent management platforms (CMP) like Usercentrics Web CMP provide notifications about data collection and processing on websites or apps and enable users to make consent choices, as well as signaling of those consent choices to other systems.

Use security best practices like access controls

As with other personal information collected during marketing, ecommerce, or other operations, restrict which staff has access to what data based on the necessities of their roles. Limit who can access call recordings or chat logs, e.g. for training or support escalation. This reduces the risk of unauthorized access or use.

Monitor and regularly review data, security, and privacy operations

Regularly audit and update your recording and data-gathering practices to help ensure continued compliance with CIPA, especially as technologies and privacy expectations evolve.

Ensure that you’re providing clear notifications and are only collecting the data you need for specific purposes. Limit who has access to that data, and follow strict retention policies so you don’t store it longer than necessary or use it for purposes for which users have not been notified or given the option to opt out.

CIPA enforcement

Unlike many state-level data privacy laws, CIPA has a number of enforcement bodies and mechanisms. This is not surprising given penalties can be civil or criminal, and because unlawful monitoring or recording can take place across many companies and industries, or even among individuals.

Typically, both criminal and civil actions must be undertaken within one year of discovering a violation. Enforcement bodies include:

- California Attorney General

- State agencies with specific industry jurisdiction for regulatory oversight

- County district attorneys

- Other authorized agencies

- Individual plaintiffs (and retained legal counsel)

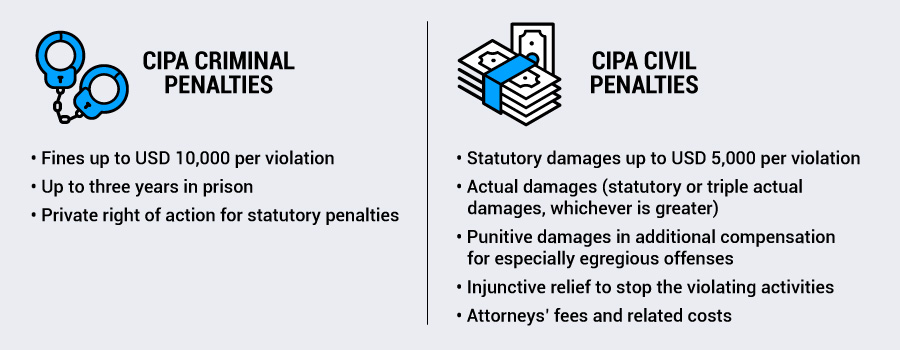

CIPA criminal penalties

Penalties for violators of the CIPA law can be hefty, and can be combined. They include:

- Fines up to USD 10,000 per violation

- Up to three years in prison

- Private right of action for statutory penalties

Criminal prosecutors can charge offences as felonies or misdemeanors, depending on the specifics of each case. A misdemeanor could bring fines of up to USD 2,500 per violation and one year in prison. A felony could increase the prison sentence up to three years.

CIPA civil penalties

As noted, individuals also have more civil recourse under CIPA than under some other privacy laws. These penalties include:

- Statutory damages up to USD 5,000 per violation

- Actual damages (statutory or triple actual damages, whichever is greater)

- Punitive damages in additional compensation for especially egregious offenses

- Injunctive relief to stop the violating activities

- Attorneys’ fees and related costs

There may also be overlaps in cases of invasion of privacy and right of publicity claims, so individuals could also be able to file a right of publicity lawsuit, claiming that the business attempted to profit from their conversations without consent.

The evolution of consent management and the California Invasion of Privacy Act

Despite being nearly 60 years old, CIPA and other “wiretapping laws” are anything but irrelevant in the digital age. According to the Fisher Philips law firm, as of February 2025, 1,641 digital wiretapping lawsuits have been filed in 28 states since June 2022, with 1,361 filed in California alone – 83 percent of all claims.

CIPA is one of the regulations and laws alleged to have been violated by the companies named in six recent class action lawsuits, for unauthorized interception of electronic communications and unlawful use of a pen register.

It can be hard for companies to keep up with ever-changing regulations and technologies, especially smaller organizations. But the consequences of not doing so can be harsh and long-lasting.

There are potential criminal and civil penalties, as well as loss of brand reputation, ongoing demands of compliance monitoring by authorities, and the risk of scaring off advertisers, investors, and other partners, damaging growth opportunities.

Using the right tools for consent management and notifications won’t enable your company to entirely ignore legal requirements around data privacy, but a robust consent management platform will help you achieve and maintain compliance as the law and technologies you use change.

It will also show your customers that you respect their privacy and rights to control access to their data, which builds long-term trust.

In April 2025 the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Europe released its first version of the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) Compliance Report, looking back at analysis for 2024.

We look at the data analysis and results for compliance levels, common issues, CMP adoption, cross-platform prevalence, and more. We’ll also discuss takeaways and what can be expected for 2025.

What is the TCF?

To provide a bit of overview, the Transparency & Consent Framework (TCF) was launched in 2017. It’s a standard developed by IAB Europe to help digital advertising stakeholders comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and ePrivacy Directive (ePD) in the European Union.

The TCF provides a unified framework that enables website publishers, advertisers, and technology vendors to communicate end users’ consent choices for data processing purposes.

The GDPR requires entities that collect and process individuals’ personal data to obtain explicit consent in many cases before processing begins.

Legitimate interest can also be a viable legal basis, and when consent would not be required, though organizations must be able to justify its use in case of inquiry by data protection authorities.

The TCF uses standardized signals to enable end users to provide or deny consent for data collection, processing, and personalized advertising. This helps to ensure transparency and accountability across the EU digital advertising supply chain.

It takes guidance from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) and EU Member States’ Data Protection Authorities (DPA), and the latest version is the TCF v2.2.

TCF stakeholders: Publishers

This includes owners and/or operators of platforms for online content or services, which may or may not be ad-supported. Publishers’ platforms collect visitors and customers’ personal data, which is typically processed by third-party Vendors for digital advertising, audience measurement, and/or content personalization.

TCF stakeholders: Vendors

Vendors include a variety of third-party companies that contract with controllers that provide the data in order for those Vendors to perform specific processing operations. For example, ad servers, measurement providers, advertising agencies, demand-side platforms (DSPs), supply-side platforms (SSPs), etc.

TCF stakeholders: Consent management platforms (CMP)

CMPs are software solutions that enable companies to meet data privacy regulation requirements on websites, apps, and connected platforms like TV. They can display cookie banners, collect and store consent preferences, block cookies and trackers until consent is obtained, populate privacy policies, and more. When using the TCF, CMPs also become responsible for consent signals between Vendors and Publishers.

TCF standardized purposes for Vendors

The TCF includes 11 standardized purposes that outline how Publishers, websites, or other sources use collected user data, with the goal of helping enable data privacy compliance.

- Store and/or access information on a device

- Use limited data to select advertising

- Create profiles for personalized advertising

- Use profiles to select personalized advertising

- Create profiles to personalize content

- Use profiles to select personalized content

- Measure advertising performance

- Measure content performance

- Understand audiences through statistics or combinations of data from different sources

- Develop and improve services

- Use limited data to select content

What is the IAB Europe TCF Compliance Report?

The TCF compliance report is an overview of how organizations implemented TCF v2.2 in 2024 (the last full calendar year), which platforms CMPs were registered for, which Purposes Vendors are using, auditing mechanisms, and whether implementations have been compliant with TCF requirements.

The Compliance Report is also a mechanism by which IAB Europe can work to ensure that the stakeholders comply with TCF specifications and policies, and how much room there still is for improvement.

Who was included in the TCF Compliance Report analysis?

There were 885 Vendors and 177 CMPs registered with the TCF by the end of 2024. Over the course of that year, 125 new Vendors and 36 new CMPs (25 percent increase from 2023) were audited and certified for the TCF. 11 existing CMPs were audited and certified for different technical environments.

Which purposes are most important to Vendors?

In 2024, the most used purpose was Purpose 1, with 708 Vendors using it. The lowest adoption was of Purpose 11, with 101 Vendors using that.

167 Vendors — 19 percent of participants — did not declare any advertising related purposes (Purposes 2, 3, 4, or 7). This indicates that some Vendors do not operate in digital advertising, but instead use the TCF for content-related purposes or measurement.

Registered CMPs

While TCF has 177 registered CMPs, 41 percent of these are private to specific Publishers. And only 5% of the CMP’s support both web, mobile and CTV – leaving a limited option to select for companies that work in multiple contexts.

- 66.7% web only

- 17.2% web and mobile (apps)

- 8.6% mobile only (apps)

- 4.8% web, mobile, and CTV

- 2.2% CTV only

- 0.5% mobile and CTV

What data privacy issues did the TCF Compliance Report find?

IAB Europe is the managing organization for the TCF, so is responsible for imposing noncompliance penalties under the TCF Terms and Conditions.

There were approximately 80 audits of CMPs, which revealed a number of gaps. As a result IAB Europe carried out 40 enforcement procedures for CMPs following reports of noncompliance from end users or TCF participants or proactive live monitoring of the CMPs’ installations.

When noncompliance is found with a CMP live installation, there are two potential procedures.

Procedure 1: More serious infringement when the CMP is found to be tampering with TC Strings. If four instances are found within a 12-month period the CMP will be permanently suspended from the TCF.

Procedure 2: When the CMP is found in breach of TCF Policies. If four instances are found within a 12-month period the CMP will be temporarily suspended from the TCF for at least two weeks.

No CMPs were suspended in 2024, and enforcement issues were resolved. The most frequent compliance failures were:

50% failure: Policy Check 9 — Not clearly informing users how to withdraw consent

42% failure: Policy Check 31 — Users unable to easily resurface the CMP UI

42% failure: Policy Check 32 — Withdrawal of consent harder than giving consent

20% failure: Technical Check 7 — Not using the current or penultimate version of the Global Vendor List

For more detail on the identified issues and key findings of these checks, please refer to Section 3.3 of the full Compliance Report. The Usercentrics CMPs comply with all of these checks.

There were 269 enforcement procedures against Vendors following monitoring or noncompliance reports, and 23 of them faced temporary suspensions until issues were resolved.

Two of the most common issues were incorrect Device Storage URLs (168 cases and 17 temporary suspensions) and incorrect Privacy Policy URLs (84 cases and six temporary suspensions.)

TCF adoption and compliance in 2025

IAB Europe is continuously increasing their efforts to ensure that the TCF is being used compliantly. This is already having a positive impact, as TCF adoption has increased over the last few years.

There’s been significant growth in adoption in Apps and CTV, as well as with ecommerce businesses adopting the TCF standard to support Retail Media initiatives.

Enforcement against Vendors has ramped up in the first half of 2025, with 175 Vendor enforcement procedures by April.

There has been investment in a new auditing tool for apps to align with web procedures, and to remove the manual checks that have been required to date.

Additionally, there is a push for more automation of enforcement processes, and Publishers have been encouraged to use noncompliance reporting tools to flag issues more quickly.

Year over year, TCF registration and adoption has been displaying a healthy growth rate, and enforcement has enabled rapid and sustainable correction of issues to ensure Vendors and CMPs are implementing the TCF compliantly.

Google already requires implementation of a certified CMP to serve ads in the EU — and Usercentrics CMPs were among the first to achieve certification — and it’s likely that further privacy-led policies will follow as data privacy regulations expand and evolve.

It makes competitive and growth-centric sense for CMPs to be TCF-registered and compliant, and for companies to use these tools as part of their Privacy-Led Marketing strategy to meet the requirements of regulations and tech partners’ policies, and to build trust with audiences.

What’s the smallest GDPR fine you’ve heard of? Can you even remember? Probably not, since the headlines only tend to capture the truly eye-popping ones.

But does that mean that Data Protection Authorities (DPA) don’t bother checking up on smaller companies’ GDPR compliance? Can your business safely ignore GDPR compliance requirements?

We don’t recommend it. And not just because we at Usercentrics preach data privacy, Privacy-Led Marketing, and consent management solutions. It’s because there’s a lot more GDPR compliance enforcement happening than you may realize, and has been for years.

(The smallest recorded GDPR fine to date was issued in 2020 to a Hungarian entity for EUR 28.)

Who enforces the GDPR?

While the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) applies to residents of and organizations operating in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA), enforcement doesn’t fall under a single entity.

There is the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). Each EU Member State has a DPA — hence why they’re also called National Supervisory Authorities — and all of those DPAs make up the EDPB, along with the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS).

Each country in the EU is responsible for investigating and correcting GDPR violations and levying penalties on the organizations responsible where appropriate.

What do Data Protection Authorities do?

DPAs don’t just issue fines. They try to prevent them in the first instance. These authorities are involved in the full privacy compliance lifecycle, with their functions divided into three main categories: advisory, investigative, and corrective.

DPA advisory powers and functions

- Provide expert guidance to national governments, organizations, and individuals on data protection matters

- Offer opinions on proposed legislation and administrative measures that affect personal data processing

- Advise organizations on their compliance obligations

- Promote public awareness of data protection rights and best practices

- Contribute to the development of codes of conduct and certifications

- Issue recommendations for consistent GDPR application across the EU

DPA investigative powers and functions

- Conduct audits and review data protection impact assessments (DPIA)

- Perform on-site inspections and access premises, equipment, personal data, and processing information

- Perform ongoing audits to ensure continued compliance after a violation

DPA corrective powers and functions

- Issue warnings, corrective measures, and reprimands for violations

- Restrict or ban data processing activities

- Order the rectification or deletion of personal data

- Suspend data transfers to third countries

- Impose administrative fines for violations

- Refer cases to the courts

What are the penalties for GDPR violations?

Under the GDPR there is a two-tiered system for administrative penalties. In addition to orders for corrective measures, organizations can be fined for violations.

The first tier is generally for less severe or first-time violations, and is up to EUR 10 million or two percent of global annual revenue, whichever is greater.

An example of a first-tier fine is Italian DPA Garante fining satellite TV platform Sky Italia EUR 842,062 in 2024 for unlawful telemarketing activities.

The second tier is generally for more serious or repeat violations, and is up to EUR 20 million or four percent of global annual revenue, whichever is greater.

The highest GDPR fine issued to date was a second-tier fine for Meta Platforms Ireland (parent company of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) for EUR 1.2 billion in 2023 for unlawful personal data transfers to the United States.

The most common cause of violations is Art. 5 GDPR, principles relating to processing of personal data. This includes issues like not having a valid legal basis for data processing, not being transparent about data processing or data subjects’ rights, or processing data for purposes beyond those communicated and covered under the chosen legal basis.

Fines are at DPAs’ discretion, and are not mandatory. Organizations can be warned or provided with a “cure period” during which they can correct noncompliance issues without facing fines. However, fines can also be issued along with other measures, like orders to stop data processing or to delete data.

What is shadow enforcement of the GDPR?

As noted, DPAs are doing plenty of GDPR enforcement that doesn’t make headlines. The billion-dollar fines may seem completely unrelatable to the average business owner, but it’s worth noting that big tech platforms can generally afford those fines more than SMBs can afford even much smaller potential noncompliance fines they might be issued.

In addition to fines, smaller organizations also don’t tend to have a lot of available resources for some of the other possible corrective functions that could be ordered after a violation or complaint, like providing information about data processing, submitting to repeated audits, performing DPIA, and other activities.

Various types of GDPR enforcement that make up the bulk of their actions but don’t make the headlines include warnings, sanctions, sub-billion-Euro fines, audits, and other activities.

France’s CNIL and enforcement for 2024

Let’s look at France’s DPA, the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL), which is one of the more prominent and strict DPAs. In February 2025 they published their report on sanctions and corrective measures under their jurisdiction for 2024, with increases across the board compared to 2023 (except for fines, which were EUR 90 million in 2023.)

For 2024, the CNIL made 331 decisions, resulting in:

- 87 sanctions

- 180 compliance orders

- 64 reprimands

- 75 fines

- 14 fines with injunction under penalty, meaning an additional daily fine until the organization pays the imposed fine

- 7 decisions adopted in cooperation with other EU DPAs

- over EUR 55,212,400 in fines

As in 2023, failing to cooperate with the CNIL, e.g. not responding to the CNIL’s requests, was the most common reason for sanctions in simplified procedure cases (the procedure used for straightforward violation cases).

The CNIL’s decisions were for issues as varied as ads in emails, anonymization of healthcare data, failing to minimize data collection, and warnings to government departments to ensure personal data stored in their databases is accurate.

That’s a fair bit of activity, but what’s really notable is how many of those decisions were made public: only 12, or 3.6 percent. 96.4 percent of all of the CNIL’s GDPR compliance decisions were “shadow” enforcement.

A person reading the headlines or even doing some deeper digging into GDPR enforcement would have found almost none of that information. No wonder a lot of organizations still think GDPR requirements aren’t a concern.

It’s a bit ironic keeping so much enforcement quiet, given that DPAs’ mandate includes functions not only meant to correct violations, but to ensure companies know their responsibilities and comply with them to prevent violations.

Why so much GDPR enforcement is not publicized

Perhaps the most basic reason why most GDPR enforcement doesn’t make headlines, or get any coverage, is that it’s not that interesting or would take too much explaining to make the issues clear to the average person.

Attention spans, especially online, do not favor long, dry regulatory explanations.

Maybe if your main competitor was fined EUR 100,000 over noncompliant marketing practices, it would pique your interest, but to the media at large it’s not that exciting, and most of the companies fined are not likely ones you’ve heard of.

Not like a billion-Euro fine and/or a global tech giant, which is a lot of money by pretty much anyone’s standards for companies everyone’s heard of and whose platforms or services are used by billions of people.

Other reasons could include confidentiality. A violation becoming public could have a significant negative impact on brand reputation. Certain issues like data breaches require notifications, e.g. of authorities and affected customers but not all of them.

That information could be used by competitors, and could scare off potential customers, advertisers, partners, or investors, even if the issue has been rectified.

Many issues are relatively minor and can be fixed fairly quickly, without incurring fines or other significant penalties. Those leave little to talk about.

In some larger or trickier cases, investigations may be ongoing, so can’t be talked about or publicized for some time.

How organizations can achieve and maintain GDPR compliance

GDPR compliance responsibilities can be complex, but compliance doesn’t have to be. There are robust tools that are budget-friendly, don’t require a lot of resources to set up or maintain, and grow with your organization.

One of the most common GDPR violations is not meeting requirements to collect and process personal data. While other legal bases may seem more convenient to companies, users’ consent is the one that is required in many cases.

A consent management platform enables organizations of all sizes to achieve cookie compliance by obtaining informed, explicit consent. It enables transparency about your data processing and securely stores consent information in case of a DPA inquiry or audit.

In addition to avoiding fines and other penalties from DPAs, companies gain benefits from data privacy compliance. Protect advertising revenue and ensure continued use of major tech platforms’ services, like Google Ads or Analytics.

Show your customers and prospects that you respect their privacy and give them control over their personal data. This builds trust, which leads to long-term engagement and customer loyalty.

Future-proof your marketing strategies by moving away from outdated data sources like third-party cookies. Zero- and first-party data comes right from your users with their consent, so it’s higher quality and enables GDPR-compliant use for your Privacy-Led Marketing.

Data Protection Authorities in the EU can’t explicitly endorse individual consent management platforms, but they do recognize the importance of consent management in ongoing GDPR compliance efforts.

The cookieless future is no longer a concept — it’s here. While Google paused its full phase-out of third-party cookies in Chrome in 2024, other major browsers like Safari and Firefox have already eliminated them. That means marketers can’t afford to wait.

However, the cookieless future doesn’t mean there won’t be cookies of any kind in use. It just means that third-party cookies and their sometimes indiscriminate tracking will be phased out. While marketers have long relied on the data third-party cookies collect, it has often been collected with questionable consent or without any consent at all. The data is also often of lower quality and needs to be aggregated with other data sources to be useful and profitable.

As we say goodbye to third-party cookies, let’s delve into the resulting changes in requirements, the impact of this shift, and how to future-proof your marketing strategy.

What is a cookieless future?

A cookieless future refers to the shift away from using third-party cookies. This change doesn’t mean the end of cookies altogether; first-party cookies will still play a vital role for marketers. But this change marks a departure from invasive tracking practices that compromise user privacy.

In a cookieless future, marketers will rely more on zero-party data, which is explicitly shared by users, first-party data, which is collected directly from user interactions, and consent-based technologies. It also involves new methods like contextual advertising and privacy-enhancing technologies.

A cookieless future is not the end of digital advertising. It’s the beginning of a smarter, more privacy-conscious era where trust and transparency must be central to strategy.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small text files stored on a user’s browser that help websites remember user preferences, login status, and behavior. There are two primary types:

- First-party cookies: These are set by the website the user is visiting, and are typically used for essential site functions and analytics.

- Third-party cookies: Domains other than the one the user is visiting set these cookies, which are mainly used for cross-site tracking and ad targeting.

Marketers have long relied on third-party cookies to build audience profiles and run retargeting campaigns. However, these cookies often collect data without meaningful user consent, which raises concerns about transparency and privacy.

Learn more about how cookies differ from personal data.

Why are third-party cookies being phased out?

Third-party cookies have long been a staple of digital advertising because they enable cross-site tracking, behavioral targeting, and detailed user profiling. However, they’ve come under scrutiny due to privacy concerns and their lack of transparency.

Browsers like Safari, Firefox, and Brave started blocking third-party cookies by default as early as 2017. And Google is giving users the option to allow or block third-party cookies.

This shift is not just a browser-led initiative, it’s also driven by global data protection laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). These data privacy laws mandate greater transparency, accountability, and user control over personal data.

This movement reflects a broader shift toward user empowerment and ethical data use. Marketers must now explore cookieless tracking solutions that prioritize trust, transparency, and privacy compliance.

The impact of a cookieless future on marketers

The shift away from third-party cookies is reshaping digital marketing. Since marketers have long relied on these tools, they now face a series of challenges that demand adaptation.

Reduced audience visibility and segmentation

Without third-party cookies, it’s harder to identify user interests across websites. This limits marketing teams’ ability to create detailed audience segments and reach people based on behavior across platforms.

The shift to first-party and zero-party data means marketers need to rely on information users choose to share. While this data is more limited, it tends to be more accurate and useful. That means even with less of it, you can still gain meaningful insights.

Personalization becomes more challenging

Personalization used to rely heavily on tracking users’ past behavior across the web. Now, that level of insight requires users to directly share preferences or interact meaningfully with your brand. If you don’t have a strategy to collect and act on this kind of data, personalized content and ads will be less effective.

Measurement and attribution are disrupted

Standard attribution models built on third-party data no longer work. It’s harder to see how users move between devices or platforms before converting, which makes it difficult to measure the impact of different channels. Fortunately, there are privacy-compliant ways to fill these gaps, like using anonymized data, modeled conversion paths, and newer tools that help estimate performance even when tracking is limited.

Growing need for trust and transparency

People are more aware than ever of how their data is collected and used. Thanks to changing regulations and rising expectations, users now want clear explanations and meaningful benefits in return for sharing their data. If a brand can’t offer that, or doesn’t appear trustworthy, users are more likely to opt out or take their business elsewhere.

The numbers don’t lie. If you’re curious to learn more, here are 150+ data privacy statistics you need to know about.

Shift from volume to strategy

The outdated approach of collecting as much data as possible and figuring out how to use it later is no longer acceptable. Today, marketers need a more deliberate strategy. Ask users what they want to hear from you, how they want to be contacted, and what they’re comfortable sharing. Direct communication supports privacy compliance and results in better data and stronger engagement.

How to prepare for a cookieless future

Preparing for Google’s cookieless future presents an opportunity to build more sustainable, Privacy-Led Marketing strategies.

A foundational step is strengthening the collection and use of first-party and zero-party data. First-party data comes from user interactions with your digital properties. Zero-party data is information users voluntarily share, such as preferences or interests, which means it is highly accurate and based on trust.

Marketing teams must revise their marketing and advertising strategies to prioritize these sources. Doing so may include updating consent mechanisms with tools like Consent Management Platforms (CMPs) that support privacy compliance and allow for clear, customizable user choices.

Beyond data collection, marketers’ broader digital strategy must evolve. Contextual targeting — which might look like placing sports-related ads on a fitness blog — offers a non-invasive alternative to behavior-based advertising. Companies should also explore privacy-enhancing technologies that provide insights without compromising individual privacy.

The goal is not just to adapt to a cookieless future, but to lead with a marketing approach that builds trust. That means offering clear value exchanges, following ethical data practices, and committing to responsible, long-term data use.

Curious to learn more? Check out our detailed guide about privacy-first marketing.

Strategies for data collection in a cookieless world

In a cookieless future, data collection must be more intentional and privacy-conscious. Marketers need strategies that prioritize consent and transparency from the outset to build a foundation of trust while still enabling effective personalization.

Zero-party data is shared proactively by users through channels like surveys, preference centers, and feedback forms. Because this data comes directly from the source, it tends to be more accurate, reliable, and effective for segmentation and personalization. Encouraging users to share this data requires offering clear value exchanges, such as more relevant content or product recommendations.

First-party data, collected through direct interactions like purchases, logins, and website behavior, is equally important. Loyalty programs, gated content, and tailored user experiences are effective ways to gather this data while reinforcing engagement and brand affinity.

Marketers are also increasingly adopting data clean rooms to enable secure collaboration with partners like platforms or publishers. These environments use techniques like hashed identifiers to match audiences without sharing raw data, enabling insights while preserving user privacy.

CMPs are also helpful to collect data transparently and in compliance with privacy regulations. CMPs give users clear choices and control over how their data is used. Customizing consent experiences through layered information, region-specific settings, and accessible design can boost opt-in rates and strengthen confidence in your brand’s data practices.

By aligning data collection strategies with user expectations and evolving privacy standards, marketers can build a more resilient and trusted foundation for personalization in a cookieless world.

Implementing cookieless tracking solutions

Implementing cookieless tracking solutions can help you retain campaign measurement and user insights while respecting privacy norms. These solutions prioritize consent, transparency, and secure data handling.

These solutions are built around consent-first frameworks. That means data collection must be legally compliant and ethically sound, goals that align with both regional laws and user expectations. These frameworks require clear user permissions before any data is processed or activated, and are increasingly supported by mechanisms built into CMPs.

Server-side tagging also plays a key role. It shifts data processing from the user’s browser to secure, cloud-based servers, reducing reliance on browser-stored identifiers that are often blocked or restricted. This approach improves data accuracy, control, and resilience.

“Server-Side Tagging is a mechanism where tracking tags — pixels, scripts, analytics events — are managed and executed on a server-side environment rather than directly in the user’s browser.”

— Tom Wilkinson, Senior Marketing Consultant

Read more about the details of Server-Side Tagging and tracking.

Similarly, event-based measurement focuses on tracking meaningful user interactions, such as clicks, video views, scroll depth, or form completions, within your digital properties. These first-party events, captured with user consent, offer actionable insights without relying on third-party tracking.

To fully embrace these solutions, marketers can integrate tracking with a CMP and Customer Data Platforms (CDPs). CMPs manage permissions and help ensure user choices are respected across systems. CDPs centralize consented user data, enabling personalization, segmentation, and analytics that stay privacy-compliant.

Cookieless attribution and measurement

Effective campaign measurement in a cookieless future demands new attribution models, as traditional multi-touch models that rely on third-party cookies become less viable.

One of the most promising alternatives is predictive modeling. This method uses machine learning algorithms to analyze patterns in available data and forecast likely user behaviors and conversions. By referencing variables like past interactions, demographics, and contextual signals, predictive models can estimate the likelihood of specific actions, such as a purchase or an engagement. This approach works without requiring cookies or personal identifiers, relying instead on aggregate data and privacy-safe signals.

Conversion modeling is being prioritized by platforms like Google. It estimates conversions that cannot be directly observed using privacy-safe signals. This approach is central to Google’s evolving measurement tools. In fact, Google supports this shift with tools such as Google Consent Mode, Enhanced Conversions, Server-Side Tagging, and Customer Match. These technologies are designed to maintain insight integrity while aligning with shifting privacy standards.

Media mix modeling (MMM) offers another approach. It evaluates the impact of various marketing channels based on aggregated data, helping marketers allocate budget effectively even without individual user tracking.

Another emerging approach is server-side tracking (SST), which shifts data processing from the user’s browser to the server. This can improve data accuracy, mitigate signal loss from browser restrictions or ad blockers, and support compliance with privacy regulations.

Usercentrics’ server-side tracking solution is built with these priorities in mind. It enables organizations to maintain essential measurement capabilities in a privacy-conscious, configurable environment—without relying on third-party cookies.

Cookieless advertising

Let’s not forget the phase out of third-party cookies. Fortunately, there are cookieless advertising options that still deliver results.

One method is contextual advertising, which uses the content of a web page, rather than user behavior, to determine ad placement. By aligning ads with the content on the page, this approach supports both relevance and privacy, making it a natural fit for the cookieless era.

Identity solutions are also emerging to bridge the personalization gap. Technologies like Unified ID 2.0 and platforms such as LiveRamp use encrypted, email-based identifiers to enable privacy-conscious targeted advertising. These tools help preserve capabilities like personalization, audience segmentation, and frequency capping without relying on invasive tracking methods.

Another alternative is cohort-based targeting through tools like Google’s Topics API. This tool groups users based on shared interests rather than individual behavior. This method maintains a degree of audience targeting while protecting user anonymity.

As targeting methods shift, advertisers will also need to rethink their creative strategies. Without behavioral data to guide personalization, success will require a deeper understanding of context and the ability to craft messaging that fits naturally within the surrounding content.

Aligning marketing and privacy teams

To thrive in a cookieless future, marketing teams need to embrace Privacy-Led Marketing strategies and technologies. Data privacy compliance cannot be an afterthought, it must be integrated into campaign planning, technology selection, and performance reporting.

Strategies should focus on:

This shift enables not only regulatory compliance but also better engagement, higher-quality insights, and more resilient data strategies.

What’s next in a cookieless world?

The shift away from third-party cookies is a turning point in how businesses approach privacy, compliance, and user trust. Regulations like the GDPR, the ePrivacy Directive, and others are driving the need for more transparent data practices, and browsers are enforcing these changes with stricter tracking limitations.