In the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been in effect since May 2018. Its goal is to protect EU residents’ privacy and personal data and give them control over how that data is used.

Since its implementation, the GDPR has become the world’s most influential data privacy law, impacting legislation in other countries and significantly affecting how companies do business in Europe.

One of the most newsworthy aspects of GDPR enforcement is the fines levied against companies found to have violated the law.

Organizations of any size can be fined for violations, but the news stories that make headlines often involve tech giants with global reach and billions of users. Fines for misusing personal data in those cases have risen into the billions.

Who is responsible for GDPR compliance?

There are several levels of responsibility for General Data Protection Regulation compliance, and their degree of responsibility varies based on various factors.

These can include the type of data processing or whether they’re an entity requesting personal data and using it for stated purposes, or a third-party entity working for someone else.

At a more granular level, there are often privacy experts within organizations who are responsible for data privacy operations. In some cases, appointing a Data Protection Officer is a legal requirement.

Data controllers and data processors

Data controllers and data processors are people or organizations actually collecting and processing the personal data of EU residents. This processing can include using, sharing, or selling data.

Those entities have day-to-day responsibility for data privacy and security. They must have a viable legal basis for collecting data, use that data per GDPR guidelines, and only for the purpose(s) they communicate, maintain reasonable security, and inform data subjects about their rights and the use of their data.

Data controllers’ responsibilities require them to:

- Securely maintain records of consent preferences

- Maintain data accuracy

- Respond to data-related requests, including requests for correction or deletion (with exceptions)

- Implement and maintain reasonable organizational and technical measures for data protection

Data processors, on the other hand, typically work for data controllers. An example would be a third-party vendor handling advertising or communications for a company. Data processors’ responsibilities include:

- Implementing appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect data

- Notifying the data controller of any data breaches

- Keeping records of their processing activities

- Complying with opt-out or data deletion requests after processing has started

While both controllers and processors have responsibilities under the GDPR, ultimately, data security and privacy compliance responsibilities belong to the controller.

Data protection authorities

Each EU member state has its own authoritative body to investigate alleged violations and enforce compliance with the GDPR. These independent public agencies are known as data protection authorities (DPAs). These organizations also enforce other local or regional privacy-related laws.

Read more about who is responsible for GDPR compliance within your company.

What is considered a violation under the GDPR?

A violation of the GDPR occurs when a data controller or processor fails to meet one or more of the regulation’s requirements. Violations range from administrative oversights to serious breaches of data protection principles. Examples include:

- Failing to obtain valid consent before collecting or processing personal data

- Not notifying data protection authorities and affected individuals of a data breach within the required timeframe

- Collecting or using personal data for purposes not disclosed to the user, including if the original purposes change

- Failing to implement appropriate security measures to protect data

- Not providing users with access to their personal data or the ability to delete it

Even well-meaning companies can be fined if they neglect basic privacy practices or are unaware of their compliance obligations. These kinds of oversights — intentional or not — are exactly what regulators look for when deciding whether a fine is warranted.

Small oversights in privacy practices can trigger scrutiny, especially if they are repeated or ongoing. This is why it’s crucial to understand your organization’s responsibilities, especially when violations lead to financial penalties and reputational damage.

What are the criteria for imposing GDPR fines?

When a breach is identified, data protection authorities evaluate certain criteria to determine the appropriate fine. These include:

- Nature, gravity, and duration of the infringement

- Whether the violation was intentional, negligent, or repeated

- Any action taken by the organization to mitigate the damage

- Degree of cooperation with authorities during investigations

- Categories of personal data affected

- Any previous infringements by the organization

- How the supervisory authority became aware of the infringement

- Whether the company followed approved codes of conduct or certification mechanisms

This framework seeks to make fines proportionate to the offense and consider each case’s unique circumstances.

What are fines and penalties under GDPR?

If an organization that processes personal data belonging to EU residents is found to have violated the GDPR, there are several types of potential penalties, outlined in Art. 83 GDPR.

Data protection authorities can impose administrative fines, including the maximum penalty for a GDPR breach, depending on the severity. Beyond fines, the DPA can:

- Issue warnings or reprimands

- Temporarily or permanently impose restrictions on data processing

- Order the erasure of personal data

- Suspend international data transfers to third countries

- Impose administrative fines

- Impose criminal penalties

Administrative fines are probably the most well-known penalty of the GDPR. There are two levels of administrative fines, depending on the severity of the infraction.

Tier one administrative fines

First-tier GDPR fines are generally for first-time or less severe infractions. They can be up to EUR 10 million per infraction or two percent of global annual revenue for the preceding financial year, whichever is greater.

Tier two administration fines

Second-tier GDPR fines are generally for repeat violators or more severe infractions. They can be up to EUR 20 million per infraction or four percent of global annual revenue for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher. These maximum GDPR fines are high because they are reserved for serious or repeat offenses.

Who can be fined under the GDPR?

Any organization that processes the data of EU residents and fails to comply with GDPR requirements can be fined, whether or not the entity is also located in the EU.

This includes data controllers and processors or joint controllers, applicable when two or more entities jointly determine the purposes and means of processing personal data.

While violations tend to affect commercial entities, other types of organizations can be fined for data privacy violations under the GDPR as well. This includes nonprofit organizations and charities. Few are exempt from GDPR penalties.

Enforcement action against smaller entities is also more common than many people think, largely because only massive fines levied against big tech companies tend to garner headlines.

However, even a fine of less than a billion dollars can be a substantial financial hit for a small business.

Can data processors be fined under GDPR?

In short, yes. Data processors process personal data on behalf of and under the instruction and authority of data controllers, but are not immune from penalties.

GDPR compliance failures for data processors could include not implementing appropriate security measures, processing data for purposes not stated or for which there is not a valid legal basis, or failing to work with the data controller to fulfill obligations under the GDPR.

Can employees be fined under the GDPR?

Generally, employees of organizations would not be fined under the GDPR, as responsibility tends to fall on the company (controller) or the data processor(s), not individuals.

Employees certainly play a role in GDPR compliance, and can be partly responsible for a violation, like a data breach. Where there is a deliberate or recklessly damaging action that results in a GDPR violation, an employee could be subject to disciplinary action by their employer, and could be penalized by other relevant laws.

Organizations are expected to provide employees with appropriate training and guidelines for data security and handling, and companies should have clear, accessible policies in place around data access, security, and related concerns.

Can individuals be fined under GDPR?

Private persons cannot be fined under the GDPR, but can be held liable for actions or negligence regarding data protection. Many countries have additional data privacy and security laws, and individuals involved in a data breach, for example, could face criminal or civil legal consequences.

How many companies have been fined for GDPR?

There have been hundreds of thousands of breach notifications sent to organizations under GDPR rules. Enforcement activity has been increasing each year since the law came into effect in 2018.

According to the GDPR Enforcement Tracker, authorities continue to issue GDPR fines at a steady rate. More than 2,200 fines have been recorded, and the total number of fines is growing.

Spain has issued the most GDPR fines to date, with at least 899 fines totaling over EUR 82 million. However, Ireland leads in the total value of fines, having imposed approximately EUR 3.5 billion in penalties across about 25 cases, mostly targeting major technology companies with EU headquarters located there.

What is the biggest GDPR fine to date?

To date, the maximum fine for a data breach was issued on May 22, 2023. Ireland’s Data Protection Commission issued a new record-largest GDPR fine of EUR 1.2 billion (USD 1.3 billion) to Meta (Meta Platforms, Inc.), parent company of social platforms Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Threads, and other services. This fine exceeds the previous maximum GDPR fine issued to Amazon Europe in 2021 by EUR 454 million.

Meta was also ordered to stop transferring data from Facebook users in Europe to the United States.

The reason for the ruling was that Meta’s transfers of Facebook users’ data to the US violated the GDPR’s international data transfer guidelines.

The US and EU were without an adequate agreement for data transfers for a couple of years following the court ruling invalidating the EU/US Privacy Shield. However, a new agreement was finalized in 2023, and the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework came into effect on July 10.

There are new concerns in light of changes made by the current US government administration, however, which once again put adequacy agreements between the EU and US into question.

What happens when the GDPR is breached?

When a GDPR breach occurs, the affected organization must act quickly. Under the regulation, any personal data breach that may pose a risk to individuals’ rights and freedoms must be reported to the relevant data protection authority within 72 hours.

In some cases, the organization must also inform affected individuals without undue delay.

The breach response process typically includes:

- Investigating the cause and scope of the breach

- Notifying the appropriate authorities and individuals if necessary

- Taking steps to contain and mitigate the breach’s impact

- Documenting all details of the incident and the response

The supervisory authority may launch an investigation. If the organization is found to have failed in its data protection duties, fines or corrective measures may follow.

These can include warnings, orders to change data processing practices, temporary data restrictions, or the fines up to the maximum financial penalty for a GDPR breach.

Beyond financial penalties, a breach can have serious reputational, operational, and legal consequences. A swift, transparent, and effective response can help minimize damage and maintain trust.

UK GDPR fines and penalties

GDPR enforcement doesn’t stop at EU borders. Post-Brexit, the UK enforces its own version of the regulation with similar consequences.

Upon leaving the European Union on January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom adopted a near-identical version of the GDPR, commonly referred to as the UK GDPR.

Fines and penalties for noncompliance remain aligned with the original EU regulation. UK GDPR enforcement is the responsibility of the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

As with the EU GDPR, there are two tiers of fines.

Tier one administrative fines

First-tier UK GDPR fines are for first time or less severe infractions. They can be up to GBP 8.7 million or two percent of global annual revenue for the preceding financial year, whichever is greater.

Tier two administration fines

Second-tier UK GDPR fines are for repeat violators or more severe infractions. They can be up to GBP 17.5 million or four percent of global annual revenue for the preceding financial year, whichever is greater.

How to avoid GDPR fines

Whether you’re processing data belonging to residents in the EU or the UK, the most effective strategy is the same: avoid fines by prioritizing compliance from the start. Your company must understand its responsibilities to achieve and maintain compliance with the law’s requirements.

To get ahead of GDPR compliance, implement data protection and privacy best practices. In addition, consider regularly consulting with a privacy expert like a Data Protection Officer (required under the GDPR in many cases) or qualified legal counsel.

Some compliance actions are required in certain countries, but are just recommendations elsewhere. It is important to verify which requirements are applicable to your business.

There are a number of recommendations for organizations to achieve and maintain GDPR compliance and avoid fines:

- Conduct regular data audits to fully understand data collection and processing activities

- Conduct data protection impact assessments (DPIA)

- Implement data protection policies and procedures

- Train employees on GDPR compliance and data security practices

- Appoint a qualified and well-informed DPO when required, which can be an internal or external hire, as long as they have sufficient GDPR expertise

- Work with trusted third-party vendors and service providers that are GDPR-compliant, and implement contracts prior to starting data processing operations

- Use a comprehensive consent management solution to collect and store valid user consent on websites, apps, connected TV, etc.

How Usercentrics consent management can help your company

The maximum fine for a GDPR breach can be financially devastating. In the UK, the maximum financial penalty for breaching the UK GDPR is just as serious.

These aren’t rare occurrences. The large GDPR fines issued to companies like Meta and Amazon might seem unrelatable to smaller businesses, but they are not immune to consequences for violating the law.

Here’s the good news: compliance doesn’t have to be overwhelming.

Usercentrics Consent Management Platform (CMP) helps companies like yours simplify GDPR compliance. With our robust and scalable consent management solution, we make it easy to manage user consent, understand what data your website is collecting, and prove compliance when it matters most.

No legal jargon or guesswork, just clear, practical solutions to reduce your risk and support your data strategy.

Whether you’re trying to avoid the maximum penalty for a GDPR breach, prepare for audits, or simply build user trust, we give you the visibility and control you need to manage data responsibly.

Who is responsible for enforcing the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)? The answer is more complex than just regulatory authorities.

The GDPR is one of the most comprehensive data privacy laws in the world, and enforcement isn’t limited to external authorities. Responsibility for GDPR compliance belongs to organizations, departments, and even individuals.

We’ll look at who is responsible for data privacy and protection and how to implement best practices. We will also outline GDPR enforcement from a government level down to day-to-day corporate operations.

What is GDPR?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the European Union’s foundational data privacy law. It was introduced in 2016 and took effect in May 2018, replacing the 1995 Data Protection Directive. Unlike directives, which require national governments to pass their own local versions, the GDPR is a regulation that applies directly and uniformly across all EU and European Economic Area (EEA) member states.

The GDPR was designed to give individuals more control over their personal data and to align data protection laws across Europe. It governs how personal data is collected, processed, stored, shared, and deleted. It also introduces strict requirements around user consent, transparency, security, and organizational accountability.

The regulation affects any organization, regardless of location, that processes the personal data of EU residents. This means that whether you’re based in Berlin, Boston, or Bangalore, if you have users in the EU, you have to comply with the GDPR.

Learn more about the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Who is responsible for GDPR compliance in companies?

GDPR compliance is not solely the job of regulators or legal advisors. It should be built into businesses’ day-to-day operations. Two individuals hold the most responsibility: data controllers and data processors.

Data controllers, data processors, and GDPR compliance

Data controllers and data processors collect and process users’ personal data, and are thus responsible at the day-to-day level for data security and privacy.

Under the GDPR, a data controller is a person or organization that collects personal data and determines the purposes and means of its processing. Data processing can mean anything from creating customer profiles to aggregating demographic information for sale.

A data processor is a person or organization that processes personal data on behalf of a data controller. Advertising partners are a good example of data processors.

GDPR requirements apply to both data controllers and data processors, but their specific responsibilities differ. Ultimately, data security and privacy compliance are usually the controller’s responsibility, including for the actions (or negligence) of contracted processors.

This is why it’s critical, and to a degree required, to enter into clear, comprehensive contracts with all prospective data processors and to review their activities.

Responsibilities of data controllers under the GDPR

Data controllers are primarily responsible for GDPR compliance, so they must obtain valid consent, as defined in Art. 7 GDPR, from individuals for data processing. Their additional responsibilities include:

- Maintaining secure records of consent preferences

- Keeping data accurate and up to date

- Correcting or deleting data when requested, under certain circumstances

- Implementing appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect data

Data controllers must also verify with contractual agreements that any third-party data processors they work with are GDPR-compliant.

In practice, this means that the controller doesn’t just decide how data is used. They also have to demonstrate accountability at every stage of the data lifecycle. This includes transparency with users, cooperation with supervisory authorities, and full documentation of compliance measures.

In short, the data controller sets the tone for how an organization approaches data privacy and is ultimately the one who bears the most legal responsibility.

Responsibilities of data processors under the GDPR

Data processors must process personal data only according to the instructions of the contractual agreement with the data controller. Their additional responsibilities include:

- Implementing appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect data

- Notifying the data controller of any data breaches

- Keeping records of processing activities

- Compliance with data deletion requirements after processing

Processors do not have the freedom to decide how personal data is used, but they still play a critical role in keeping it safe. This includes handling data with care, applying encryption and access controls, and executing proper deletion once processing is complete.

If a data breach occurs or if a processor fails to follow the agreed upon terms, they can be held legally responsible, especially if negligence is involved. That’s why it’s crucial for processors to stay current on security best practices and to regularly review their compliance procedures.

Data Protection Authority (DPA)

Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) are independent public authorities that oversee GDPR compliance and enforcement in each EU member state. Typically, each EU member country has its own DPA that enforces the GDPR and other local or regional privacy laws, like the CNIL in France or Datatilsynet in Denmark. DPAs have the power to investigate GDPR violations, issue fines, and order organizations to take corrective actions.

Who has a duty to monitor compliance with the GDPR? DPAs, certainly, but organizations need to monitor data processing and security themselves every day. This includes which third-party vendors are handling user data.

Additionally, companies should enlist the help of legal counsel or a privacy expert to keep up with changes to the legal landscape as more countries implement and update data privacy laws.

Another way is with a consent management solution, which can help to automate compliance with the GDPR and its requirements surrounding cookies.

How does GDPR enforcement work?

GDPR enforcement is decentralized but coordinated. Each EU member state designates a national DPA to oversee compliance within its borders. These authorities investigate complaints, conduct audits, and issue penalties when organizations fail to meet GDPR requirements.

In cross-border cases — when a company operates in more than one EU country or processes data from individuals across several member states — a lead supervisory authority is appointed. This authority streamlines enforcement. Oversight is further supported by the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which helps apply the law consistently across Europe.

Enforcement can begin through various channels: user complaints, data breach notifications, proactive DPA audits, or cooperation among authorities.

DPAs have broad power to investigate, restrict processing activities, or impose corrective actions. But they also serve in an advisory role, helping organizations improve their data handling and avoid future violations.

What are the exemptions under GDPR?

While the GDPR applies broadly, there are a few specific exemptions that limit its scope in certain contexts.

- Personal or household activities: If data is processed purely for personal use, such as keeping a private contact list or sharing family photos, that processing is exempt from the GDPR.

- Law enforcement and public security: Activities involving crime prevention, national security, or public safety are typically regulated by separate legislation, such as the Law Enforcement Directive.

- Journalism, academia, art, and literature: These sectors may receive limited exemptions when data processing is necessary to balance freedom of expression with privacy rights.

Even in these cases, however, basic data protection principles apply to some degree, like fairness, transparency, and security. Organizations should seek legal advice if they believe their processing might fall into an exempt category.

What are the penalties for noncompliance with the GDPR?

GDPR penalties can be significant and reflect the severity of the violation. The regulation outlines a two-tiered structure.

- Up to EUR 10 million or two percent of the organization’s annual global turnover, whichever is greater, for violations related to record keeping, security, and data breach notifications.

- Up to EUR 20 million or four percent of global turnover, whichever is greater, for more serious breaches, such as unlawful data processing, lack of user consent, or violating data subject rights.

These fines are not automatic. DPAs take multiple factors into account when determining penalties, such as:

- Nature, gravity, and duration of the infringement

- Whether the violation was intentional or due to negligence

- Categories of data affected

- Efforts made to mitigate the damage

- Any past violations and/or history of compliance

In addition to financial penalties, data protection authorities can impose corrective actions. These may include temporary or permanent bans on processing, mandatory data deletion, or requirements to adjust data handling practices.

Reputational damage can also be substantial, another reason why proactive compliance should be both a legal and strategic priority.

The largest GDPR fine to date was issued to US-based tech company Meta — parent company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and others — in response to its handling of user data. The fine amounted to USD 1.3 billion.

EU privacy regulators gave the company five months to stop transferring data from EU-based users to the United States. The EU and US have an “on again, off again” relationship with regards to international data transfers and adequacy agreements regarding data protection.

However, unlike some other data privacy laws, the GDPR does not include a “cure period.” In some jurisdictions, organizations may be allowed time to fix issues and avoid facing penalties.

Under the GDPR, however, once a violation is identified, fines and corrective actions can be applied even if the organization remediates the issue right away.

Common GDPR compliance issues and challenges

GDPR compliance can be challenging, especially for small and medium-sized businesses. In many cases, it requires the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO). In smaller organizations, that may mean assigning those duties to someone who already holds another role.

Common compliance challenges include:

- Understanding the organization’s specific compliance responsibilities

- Obtaining valid user consent

- Setting up and maintaining a consent management solution

- Implementing appropriate data security measures

- Complying with data subject rights requests in a timely manner

- Reporting data breaches to DPAs within 72 hours

Best practices for GDPR compliance

To stay compliant, companies should follow data protection and privacy best practices. Some actions are legally required in certain countries, while in others they are only recommended. It’s important to review both GDPR and local regulatory requirements to understand what applies to your business.

Best practices include:

- Conducting audits to fully understand the data you hold and data processing activities

- Conducting data protection impact assessments

- Implementing data protection policies and procedures

- Training employees on GDPR compliance

- Appointing a qualified and well-informed DPO where required

- Working with trusted third-party vendors and service providers that are GDPR-compliant and implementing clear and comprehensive contracts before data processing begins

- Using a comprehensive consent management solution to collect and store valid user consent on websites and apps

Want to know more? Here’s everything you need to know about GDPR compliance.

GDPR responsibilities and enforcement

Data controllers and data processors each have defined roles under the GDPR, and organizations should take steps to make sure those responsibilities are being met.

That includes limiting how much personal data is collected, securing it properly and limiting access to it, and working only with trusted partners. Falling short can lead to more than just fines — it can erode user trust and hurt your reputation.

To stay on track, appoint a Data Protection Officer if needed, review your security practices, and make sure your vendor contracts are specific about data protection.

A consent management platform can also help keep things simple, enabling you to collect valid consent and stay transparent with users across your website and marketing tools.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) sets strict standards for how organizations must handle personal data collected from individuals in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). This comprehensive data protection regulation applies to all organizations that collect or process this data — regardless of where the organization is located — if they offer goods or services to EU/EEA residents or monitor their behavior.

Among its many requirements, the GDPR places specific legal obligations on how organizations may handle special categories of personal data or sensitive personal data. These data categories receive additional protections due to their potential impact on an individual’s rights and freedoms if they are misused.

In this article, we’ll look at what constitutes sensitive personal data under the GDPR, what additional protections it receives, and the steps organizations can take to achieve compliance with the GDPR’s requirements.

What is sensitive personal data under the GDPR?

Sensitive personal data includes specific categories of data that require heightened protection under the GDPR, because their misuse could significantly impact an individual’s fundamental rights and freedoms.

Under Art. 9 GDPR, sensitive personal data is:

- data revealing an individual’s racial or ethnic origin

- information related to a person’s political opinions or affiliations

- data concerning a person’s religious or philosophical beliefs

- information indicating whether a person is a member of a trade union

- data that provides unique insights into a natural person’s inherent or acquired genetic characteristics

- biometric data that can be used to uniquely identify a natural person, such as fingerprints or facial recognition data

- information regarding an individual’s past, current, or future physical or mental health

- data concerning a person’s sex life or sexual orientation

Recital 51 GDPR elaborates that the processing of photographs is not automatically considered processing of sensitive personal data. Photographs fall under the definition of biometric data only when processed through specific technical means that allow the unique identification or authentication of a natural person.

By default, the processing of sensitive personal data is prohibited under the GDPR. Organizations must meet specific conditions to lawfully handle such information.

This higher standard of protection reflects the potential risks associated with the misuse of sensitive personal data, which could lead to discrimination, privacy violations, or other forms of harm.

What is the difference between personal data and sensitive personal data?

Under the GDPR, personal data includes any information that can identify a natural person — known as a data subject under the regulation — either directly or indirectly. This may include details such as an individual’s name, phone number, email address, physical address, ID numbers, and even IP address and information collected via browser cookies.

While all personal data requires protection, sensitive personal data faces stricter processing requirements and heightened protection standards. Organizations must meet specific conditions before they can collect or process it.

The distinction lies in both the nature of the data and its potential impact if misused. Regular personal data helps identify an individual, while sensitive personal data can reveal intimate details about a person’s life, beliefs, health, financial status, or characteristics that could lead to discrimination or other serious consequences if compromised.

Conditions required for processing GDPR sensitive personal data

Under the GDPR, processing sensitive personal data is prohibited by default. However, Art. 9 GDPR outlines specific conditions under which processing is allowed.

- Explicit consent: The data subject can provide explicit consent for specific purposes, unless EU or member state law prohibits consent. Data subjects must also have the right to withdraw consent at any time (Art. 7 GDPR).

- Employment and social protection: Processing is required for employment, social security, and social protection obligations or rights under law or collective agreements.

- Vital interests: If processing protects the vital interests of the data subject or another natural person who physically or legally cannot give consent.

- Nonprofit activities: A foundation, association, or other nonprofit body with a political, philosophical, religious, or trade union aim can process sensitive data, but only in relation to members, former members, or individuals in regular contact with the organization. The data cannot be disclosed externally without consent.

- Public data: Data may be processed if the data subject has made the personal data publicly available.

- Legal claims: Processing is required for establishing, exercising, or defending legal claims, or when courts are acting in their judicial capacity.

- Substantial public interest: Processing may be necessary for substantial public interest reasons, based on law that is proportionate and includes safeguards.

- Healthcare: Processing may be required for medical purposes, including preventive or occupational medicine, medical diagnosis, providing health or social care treatment, or health or social care system management. The data must be handled by professionals bound by legal confidentiality obligations under EU or member state law, or by others subject to similar secrecy requirements.

- Public health: Processing may be necessary for public health reasons, such as ensuring high standards of quality and the safety of health care, medicinal products, or medical devices.

- Archiving and research: Processing may be required for public interest archiving, scientific or historical research, or statistical purposes.

The GDPR authorizes EU member states to implement additional rules or restrictions for processing genetic, biometric, or healthcare data. They may establish stricter standards or safeguards beyond the regulation’s requirements.

What is explicit consent under the GDPR?

Art. 4 GDPR defines consent as “any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.”

Although the GDPR does not separately define explicit consent, it does require a clear and unambiguous action from users to express their acceptance of data processing. In other words, users must take deliberate steps to consent to their personal data being collected. Pre-ticked boxes, inactivity, or implied consent through continued use of a service do not meet GDPR requirements for explicit consent.

Common examples of explicit consent mechanisms include:

- ticking an opt-in checkbox, such as selecting “I Agree” in a cookie banner

- confirming permission for marketing emails, particularly with a double opt-in process.

- permitting location tracking for a map application by responding to a direct authorization request

Additional compliance requirements for processing sensitive personal data under the GDPR

Organizations processing personal data under the GDPR must follow several core obligations. These include maintaining records of processing activities, providing transparent information on data practices, and adhering to principles such as data minimization and purpose limitation. However, processing sensitive personal data requires additional safeguards due to the potential risks involved.

Data Protection Officer (DPO)

Organizations with core activities that involve large-scale processing of sensitive personal data must appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO) under Art. 37 GDPR. The DPO may be an employee of the organization or an outside consultant.

Among other responsibilities, the DPO monitors GDPR compliance, advises on data protection obligations, and acts as a point of contact for regulatory authorities.

Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

Art. 35 GDPR requires a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) for processing operations that are likely to result in high risks to individuals’ rights and freedoms. A DPIA is particularly important when processing sensitive data on a large scale. This assessment helps organizations identify and minimize data protection risks before beginning processing activities.

Restrictions on automated processing and profiling

Art. 22 GDPR prohibits automated decision-making, including profiling, based on sensitive personal data unless one of the following applies:

- the data subject has explicitly consented

- the processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest under the law

If automated processing of sensitive personal data is permitted under these conditions, organizations must implement safeguards to protect individuals’ rights and freedoms.

Penalties for noncompliance with the GDPR

GDPR penalties are substantial. There are two tiers of fines based on the severity of the infringement or if it’s a repeat offense.

For severe infringements, organizations face fines up to:

- EUR 20 million, or

- four percent of total global annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher

Less severe violations can result in fines up to:

- EUR 10 million, or

- two percent of global annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher

While violations involving sensitive personal data are often categorized as severe, supervisory authorities will consider the specific circumstances of each case when determining penalties.

Practical steps for organizations to protect GDPR sensitive personal data

Organizations handling sensitive personal data must take proactive measures to meet GDPR requirements and protect data subjects’ rights.

Conduct data mapping

Organizations should identify and document all instances in which sensitive personal data is collected, processed, stored, or shared. This includes tracking data flows across internal systems and third-party services. A thorough data inventory helps organizations assess risks, implement appropriate safeguards, and respond to data subject requests efficiently.

Develop internal policies

Establish clear internal policies and procedures to guide employees through the proper handling of sensitive personal data. These policies should cover, among other things, data access controls, storage limitations, security protocols, and breach response procedures, as well as specific procedures for data collection, storage, processing, and deletion. Organizations should conduct regular training programs to help employees understand their responsibilities and recognize potential compliance risks.

Obtain explicit consent

The GDPR requires businesses to obtain explicit consent before processing sensitive personal data. Consent management platforms (CMPs) like Usercentrics CMP provide transparent mechanisms for users to grant or withdraw explicit consent, which enables organizations to be transparent about their data practices and maintain detailed records of consent choices.

Manage third-party relationships

Many businesses rely on third-party vendors to process sensitive personal data, so it’s essential that these partners meet GDPR standards. Organizations should implement comprehensive data processing agreements (DPAs) that define each party’s responsibilities, outline security requirements, and specify how data will be handled, stored, and deleted. Businesses should also conduct due diligence on vendors to confirm their compliance practices before engaging in data processing activities.

Perform regular audits

Conducting periodic reviews of data processing activities helps businesses identify compliance gaps and address risks before they become violations. Review consent management practices, security controls, and third-party agreements on a regular basis to maintain GDPR compliance and respond effectively to regulatory scrutiny.

Checklist for GDPR sensitive personal data handling compliance

Below is a non-exhaustive checklist to help your organization handle sensitive personal data in compliance with the GDPR. This checklist includes general data processing requirements as well as additional safeguards specific to sensitive personal data.

For advice specific to your organization, we strongly recommend consulting a qualified legal professional or data privacy expert.

- Obtain explicit consent before processing sensitive personal data. Do so using a transparent mechanism that helps data subjects understand exactly what they’re agreeing to.

- Create straightforward processes for users to withdraw consent at any time, which should be as easy as giving consent. Stop data collection or processing immediately or as soon as possible if consent is withdrawn.

- Implement robust security measures such as encryption, access controls, and anonymization to protect sensitive personal data from unauthorized access or breaches.

- Keep comprehensive records of all data processing activities involving sensitive personal data. Document the purpose, legal basis, and retention periods.

- Publish clear and accessible privacy policies that inform users how their sensitive data is collected, used, stored, and shared.

- Update your data protection policies regularly to reflect changes in processing activities, regulations, or organizational practices.

- Train employees on GDPR requirements and proper data handling procedures, emphasizing security protocols and compliance obligations.

- Create clear protocols for detecting, reporting, and responding to data breaches. Include steps for notifying affected individuals and supervisory authorities when required.

- Conduct data protection impact assessments (DPIAs) before starting new processing activities involving sensitive data.

- Determine if your organization requires a Data Protection Officer based on the scale of sensitive personal data processing.

- Verify that all external processors that handle sensitive data meet GDPR requirements through formal agreements and regular audits.

Usercentrics does not provide legal advice, and information is provided for educational purposes only. We always recommend engaging qualified legal counsel or privacy specialists regarding data privacy and protection issues and operations.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool for understanding website performance, user behavior, and traffic patterns. However, its compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been a subject of concern and controversy, particularly in the European Union (EU). The data protection authorities of several European Union (EU) countries have weighed in on privacy compliance issues with Google Analytics, with similar complaints that focus on its insufficient protections and data transfer practices.

In this article, we’ll examine the timeline of EU-US data transfers and the law, the relationship between Google Analytics and data privacy, and whether Google’s popular service is — or can be — GDPR-compliant.

Google Analytics and data transfers between the EU and US

One of the key compliance issues with Google Analytics is its storage of user data, including EU residents’ personal information, on US-based servers. Because Google is a US-owned company, the data it collects is subject to US surveillance laws, potentially creating conflicts with EU privacy rights.

The EU-US Privacy Shield was invalidated in 2020 with the Schrems II ruling, and there was no framework or Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC) in place for EU to US data transfers until September 2021 when new SCCs were implemented. These were viewed as a somewhat adequate safeguard if there were additional measures like encryption or anonymization in place to make data inaccessible by US authorities.

A wave of rulings against Google Analytics after the invalidation of the Privacy Shield

The Schrems II ruling sparked a series of legal issues and decisions by European Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), which declared the use of Google Analytics as noncompliant with the GDPR.

- Austria: Austrian DPA Datenschutzbehörde (DSB) ruled Google Analytics violated the Schrems II ruling.

- France: Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) found that the use of Google Analytics was not compliant with Art. 44 GDPR due to international data transfers without adequate protection; organizations were given one month to update their usage.

- Italy: Garante ruled that the transfer of data to the US via Google Analytics violated the GDPR and legal bases and reasonable protections were required.

- Netherlands: Dutch data protection authority AP announced investigations into two complaints against Google Analytics, with the complaints echoing issues raised in other EU countries.

- United Kingdom: Implemented the UK version of the GDPR after Brexit, UK data protection authority removed Google Analytics from its website after the Austrian ruling.

- Norway: Datatilsynet stated it would align with Austria’s decision against Google Analytics and publicly advised Norwegian companies to seek alternatives to the service.

- Denmark: Datatilsynet stated that lawful use of Google Analytics “requires the implementation of supplementary measures in addition to the settings provided by Google.” Companies that could not implement additional measures were advised to stop using Google Analytics.

- Sweden: IMY ordered four companies to stop using Google Analytics on the grounds that these companies’ additional security measures were insufficient for protecting personal data.

- European Parliament: European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) sanctioned the European Parliament for using Google Analytics on its COVID testing sites due to insufficient data protections.

A week before the Austrian ruling, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) sanctioned the European Parliament for using Google Analytics on its COVID testing sites due to insufficient data protections. This is viewed as one of the earliest post-Schrems II rulings and set the tone for additional legal complaints.

The EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework

On July 10, 2023, the European Commission adopted its adequacy decision for the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, which covers data transfers among the EU, European Economic Area (EEA) and the US in compliance with the GDPR.

The framework received some criticism from experts and stakeholders. Some privacy watchdogs, including the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), pointed out striking similarities between the new and the previous agreements, raising doubts about its efficacy in protecting EU residents’ data.

As of early 2025, the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework and adequacy for EU/U.S. data transfers are in jeopardy. President Trump fired all of the Democratic party members of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB). As a result, the number of PCLPB board members is below the threshold that enables the PCLOB to operate as an oversight body for the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework.

This action will likely undermine the legal validity of the Framework for EU authorities, particularly the courts. The EU Commission could withdraw its adequacy decision for the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, which would invalidate it. The Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) could also overturn the Commission’s adequacy decision following a legal challenge. The last option is how the preceding agreements to the Framework were struck down, e.g. with Schrems II.

Should the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework be struck down, it could have significant effects on data transfers, cloud storage, and the function of platforms based outside of the EU, like those from Google, including Analytics. At the very least, Google may be required to make further changes to the function of tools like Google Analytics, along with related data storage, to meet European privacy standards.

Google Analytics GDPR compliance?

Google Analytics 4 has several significant changes compared to Universal Analytics. The new version adopts an event-based measurement model, contrasting the session-based data model of Universal Analytics. This shift enables Google Analytics 4 to capture more granular user interactions, better capturing the customer journey across devices and platforms. Website owners can turn this off to stop it from collecting data such as city or latitude or longitude, among others. Website owners also have the option to delete user data upon request.

Another notable feature is that Google Analytics 4 does not log or store IP addresses from EU-based users. According to Google, this is part of Google Analytics 4’s EU-focused data and privacy measures. This potentially addresses one of the key privacy concerns raised by the Data Protection Authorities, which found that anonymizing IP addresses was not an adequate level of protection.

The EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework alone doesn’t make Google Analytics 4 GDPR-compliant. The framework can make data transfers to the US compliant, if they are with a certified US company, but the onus is on website owners to ensure that the data was collected in compliance with the legal requirements of the GDPR in the first place.

How to make Google Analytics GDPR compliant

1. Enable explicit or opt-in consent

All Google Analytics cookies should be set up and controlled so they only activate after users have granted explicit consent. Users should also have granular control so that they can choose to allow cookies for one purpose while rejecting cookies for another.

A consent management platform (CMP) like Usercentrics can enable blocking of the activation of services until user consent has been obtained. Google Analytics couldn’t transfer user data because it would never have collected it.

2. Use Google Consent Mode

Google Consent Mode allows websites to dynamically adjust the behavior of Google tags based on the user’s consent choices regarding cookies. This feature ensures that measurement tools, such as Google Analytics, are only used for specific purposes if the user has given their consent, even though the tags are loaded onto the webpage before the cookie consent banner appears. By implementing Google Consent Mode, websites can modify the behavior of Google tags after the user allows or rejects cookies so that it doesn’t collect data without consent.

Read about consent mode GA4 now

3. Have a detailed privacy policy and cookie policy

Website operators must provide clear, transparent data processing information for users on the website. This information is included in the privacy policy. Information related specifically to cookies should be provided in the cookie policy, with details of the Google Analytics cookies and other tracking technologies that are used on the site, including the data collected by these cookies, provider, duration and purpose. The cookie policy is often a separate document, but can be a section within the broader privacy policy.

The GDPR requires user consent to be informed, which is what the privacy policy is intended to enable. To help craft a GDPR-compliant privacy policy, extensive information on the requirements can be found in Articles 12, 13 and 14 GDPR.

4. Enter into a Data Processing Agreement with Google

A data processing agreement (DPA) is a legally binding contract and a crucial component of GDPR compliance. The DPA covers important aspects such as confidentiality, security measures and compliance, data subjects’ rights, and the security of processing. It helps to ensure that both parties understand their responsibilities and take appropriate measures to protect personal data. Google has laid down step-by-step instructions on how to accept its DPA.

Can server-side tracking make Google Analytics more privacy-friendly?

Server side tracking allows for the removal or anonymization of personally identifiable information (PII) before it reaches Google’s servers. This approach can improve data accuracy by circumventing client-side blockers, and it offers a way to better align with data protection regulations like the GDPR. By routing data through your own server first, you gain more control over what eventually gets sent to Google Analytics.

Impact of the Digital Markets Act on Google Analytics 4

The implementation of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) has had some impact on Google Analytics 4, affecting functions, data collection practices, and privacy policies. Website owners who use the platform have been encouraged to take the following steps for ongoing compliance.

- Audit your privacy policy, cookies policy and data practices.

- Conduct a data privacy audit to check compliance with GDPR, and take any corrective steps if necessary.

- Install a CMP that enables GDPR compliance to obtain valid user consent per the regulation’s requirements.

- Seek advice from qualified legal counsel and/or a privacy expert, like a Data Protection Officer, on measures required specific to your business.

Learn more about DMA compliance.

How to use Google Analytics 4 and achieve GDPR compliance with Usercentrics CMP

Taking steps to meet the conditions of Art. 7 GDPR for valid user consent, website operators must obtain explicit end-user consent for all Google Analytics cookies set by the website. Consent must be obtained before these cookies are activated and in operation. Using Usercentrics’ DPS Scanner helps identify and communicate to users all cookies and tracking services in use on websites to ensure full consent coverage options.

Next steps with Google Analytics and Usercentrics

Google Analytics helps companies pursue growth and revenue goals, so understandably, businesses are caught between not wanting to give that up, but also not wanting to risk GDPR violation penalties or the ire of their users over lax privacy or data protection.

The Usercentrics team closely monitors regulatory changes and legal rulings, makes updates to our services and posts recommendations and guidance as appropriate.

However, website operators should always get relevant legal advice from qualified counsel regarding data privacy, particularly in jurisdictions relevant to them. This includes circumstances where there could be data transfers outside of the EU to countries without adequacy agreements for data privacy protection.

As the regulatory landscape and privacy compliance requirements for companies are complex and ever-changing, we’re here to help.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is one of the strictest privacy laws globally, and since it came into effect in 2018 it has reshaped how businesses handle personal data. It has also influenced subsequent data privacy legislation around the world.

But the GDPR is more than a legal requirement, it’s also an opportunity to demonstrate to customers that you prioritize their privacy.

Although GDPR compliance may seem complex, the long-term benefits it can bring to your business are worth it. It offers an opportunity to build trust and enhance data management practices.

Below is all the essential information you need to know about GDPR compliance. From its technical requirements to the key steps to take to achieve and maintain compliance.

What is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is an EU law designed to protect individuals’ personal data and privacy. At its core, it gives people more control over how their information is collected, stored, and used. It also establishes strict requirements for companies regarding the collection and processing of personal data. And regulates organizations that handle personal data.

The GDPR replaced the Data Protection Directive in May 2018. Unlike a directive, which commonly requires individual countries to pass their own laws using the directive guidelines, the GDPR applies across all EU member states and the European Economic Area (EEA). This means that all organizations must comply with a single set of rules. Even though each member state handles its own enforcement, doing so is more consistent.

What is considered personal data under the GDPR?

Personal data under the GDPR includes any information that can identify an individual, either directly or indirectly. This includes:

- Names, addresses, and phone numbers

- Email addresses and online identifiers (e.g., IP addresses, cookie data)

- Financial data (e.g., credit card details, banking information)

- Health and biometric data

- Employment details

Sensitive personal data includes information like racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, and genetic data. It has different and more stringent requirements, like greater protections, than other personal personal data because of the harm that could occur if it is shared.

What is GDPR compliance?

Compliance with the GDPR means following the regulation’s rules for handling personal data. Organizations must ensure transparency, security, and accountability in their data processing practices. This includes obtaining user consent when required, implementing security measures, and responding to requests from data subjects.

Achieving GDPR compliance involves an ongoing combination of legal, technical, and organizational measures.

Who needs to comply with the GDPR?

If you collect or process personal data of people in the EU — whether through a website, app, or other services — you need to comply with the GDPR.

This requirement applies to companies worldwide. Even if your business isn’t physically based in the EU, offering services or products to people within the EU means you must follow GDPR compliance rules.

Understanding whether your company falls under the jurisdiction of the GDPR is the first step in protecting your business. It’s important to note that compliance isn’t determined by the size of your company but rather by how you manage and process customer data.

Do US companies have to comply with the GDPR?

Many US companies must comply with the GDPR, even if they do not have a physical presence in the EU. The regulation applies to any organization that:

- Offers goods or services to individuals in the EU, regardless of whether a payment is involved

- Monitors the behavior of individuals in the EU, such as tracking website visitors or analyzing customer data

For example, a US-based ecommerce store selling to customers in Germany must comply with the GDPR. Similarly, a marketing company using online tracking tools to analyze the behavior of European users is subject to the regulation.

Why is complying with the GDPR important?

EU GDPR compliance isn’t just about avoiding penalties, though that’s certainly a reason to take it seriously. It can also give your business a competitive edge. Demonstrating to customers that you prioritize their privacy and security builds trust and loyalty, leading to return business and recommendations.

But the benefits don’t stop with your customers. Privacy compliance helps streamline your data practices, making it easier to organize and secure data. This reduces the risk of mishandling and helps prevent data breaches, so your business remains protected. Also importantly, it reduces legal risks from data protection authorities or consumer complaints.

When implemented properly, GDPR compliance can enhance your company’s efficiency and boost your reputation, so it’s a smart investment for long-term success.

What are key GDPR compliance requirements?

The regulation sets strict rules to protect individuals’ privacy and promote transparency in how their data is used. Ignoring these rules can lead to hefty fines and serious reputational damage.

Below are key GDPR requirements companies should know about to avoid these consequences.

Data protection principles

The GDPR is built on seven core principles that guide how organizations should manage personal data:

- Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: Data must be collected and processed legally, and individuals must be clearly informed about how their information is used.

- Purpose limitation: Data can only be used for specific, legitimate purposes.

- Data minimization: Only collect the data necessary for those purposes.

- Accuracy: Organizations must keep data up to date and correct any errors.

- Storage limitation: Personal data should not be retained longer than necessary.

- Integrity and confidentiality: Strong security measures must be in place to prevent unauthorized access or breaches.

- Accountability: Businesses must not only comply with the GDPR but also be able to demonstrate their compliance.

These principles form the foundation of responsible data management and impact every aspect of GDPR compliance.

Legal bases for processing

Before processing personal data, organizations must identify a valid legal basis for doing so. There are several lawful grounds for data processing, including consent, which means that individuals explicitly agree to data processing.

Data may also be processed if it’s necessary for contractual obligations, such as fulfilling a service agreement, or to comply with a legal obligation, like adhering to tax laws or employment regulations.

In some cases, data may be processed for vital interests, such as protecting someone’s life in an emergency, or for public interest, when the data is necessary for official tasks. Legitimate interests such as fraud prevention or security can also justify processing, as long as those interests do not override individuals’ rights.

Data subject rights

The GDPR gives individuals greater control over their personal data than previous laws, via data subject rights. These rights include individuals’ ability to access their data, correct inaccuracies, and even request data deletion, commonly referred to as “the right to be forgotten.”

In certain circumstances, individuals can also restrict the processing of their data, transfer it to another service provider, or object to processing altogether.

Companies must be prepared to handle these requests in a timely manner and respect individual rights throughout the data processing lifecycle.

Documentation and accountability

Compliance requires clear documentation. Businesses must maintain records of:

- The types of data they process

- The purpose of processing

- Where data is stored

- How long data is retained

- The security measures in place to protect the data

Documentation promotes transparency and helps demonstrate compliance in case of regulatory inquiries or audits.

Data Protection Officer (DPO) requirements

Some organizations, particularly those handling large volumes of data or sensitive personal data, must appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO). The DPO oversees privacy compliance, advises on data protection policies, and acts as the main point of contact for regulators and data subjects.

Even when not legally required, having a dedicated individual who is responsible for data protection can help organizations manage risks and stay aligned with GDPR standards.

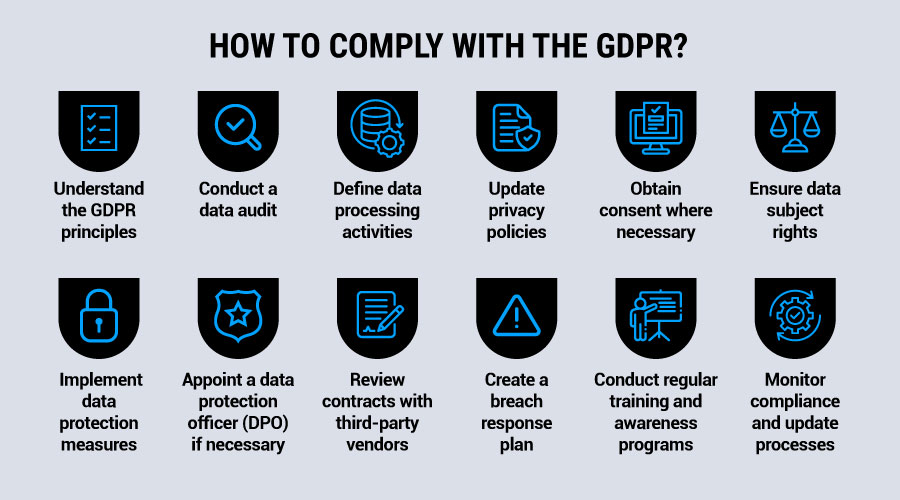

How to comply with the GDPR?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s dive into the steps your company can take to achieve GDPR compliance. While the specific approach will vary depending on your organization, there are key actions you can start taking today to meet GDPR standards.

1. Understand the GDPR principles

Start by familiarizing yourself with the core principles of the GDPR. These include lawfulness, fairness, transparency, data minimization, accuracy, and accountability. Align your processes with these principles for effective data protection.

2. Conduct a data audit

Identify all personal data you collect, store, and process, including customer, employee, and third-party data. Determine where it’s stored, how long it’s kept, and who has access. This step will help you understand and manage the data you handle.

3. Define data processing activities

Document how and why you process personal data, including the types of data and legal basis for processing. Be clear about your purposes for data collection, whether it’s for consent, contractual necessity, or legitimate interest.

4. Update privacy policies

Review and update your privacy policies to reflect GDPR requirements. Include details on the types of data collected, purposes for processing, parties that may access it, legal bases for processing, data retention, and individuals’ rights. Your policy should be easily accessible, clear for users, and updated regularly.

5. Obtain consent where necessary

If consent is your legal basis for processing, make sure it is both informed and unambiguous. Obtain consent separately from other terms and enable users to withdraw consent at any time. Track and manage consent records securely.

6. Ensure data subject rights

Implement systems to enable individuals to exercise their rights under the GDPR. These rights include access, correction, erasure, data portability, and objection to processing. Respond to these requests within the required timeframes.

7. Implement data protection measures

Apply technical and organizational measures to protect personal data. These may include encryption, access control, audits, and incident response plans. Build data protection into your systems from the outset to implement privacy by design, a concept built into GDPR requirements.

8. Appoint a data protection officer (DPO) if necessary

If your activities involve large-scale or sensitive data processing or the regular monitoring of individuals, appoint a DPO. The DPO’s job is to ensure ongoing compliance, advise on data protection issues, and act as a contact for data subjects and authorities.

9. Review contracts with third-party vendors

Ensure that you have contracts in place with third-party vendors and that they include GDPR-compliant data processing agreements. These should outline the data processed, the purpose for processing, security measures, and data retention policies. Verify that third parties also comply with the GDPR.

10. Create a breach response plan

Develop a response plan in case of a data breach. You must notify the relevant authorities within 72 hours and inform affected individuals if the breach poses a high risk. Your plan should include identification, containment, and reporting procedures.

11. Conduct regular training and awareness programs

Provide regular training on GDPR principles, data security, and breach reporting. Make sure staff understand how to handle data access requests and recognize potential breaches. Training should be ongoing to help prevent errors and promote a compliance culture.

12. Monitor compliance and update processes

Review and update your data protection practices regularly to maintain compliance. Stay informed about changes in the regulation and adapt your processes as needed. Ongoing monitoring will help you continue to meet GDPR requirements.

Technical requirements for GDPR compliance

For marketing teams handling customer data, GDPR compliance requires the right technical safeguards to keep information secure.

One key measure is data encryption. Whether you’re storing customer details in a marketing database or transferring data between platforms, encryption keeps sensitive information protected.

Email platforms, analytics tools, and customer relationship management (CRM) systems should follow current encryption standards. When sharing data with vendors, always use secure, encrypted connections.

Beyond encryption, access controls help minimize risk. Not everyone on your team needs full visibility into customer data. Your social media team may only require engagement metrics, while your email marketers need subscriber details but not full website analytics.

Setting up permissions based on necessity and enforcing strong authentication reduces exposure and strengthens security.

Even with these safeguards in place, regular security checks are essential. Periodic audits help you stay on top of access permissions, data retention settings, and inactive accounts that could pose security risks.

Having a clear process for reporting potential breaches is just as important. The GDPR requires notification within 72 hours, so a well-defined response plan can make all the difference in hitting that benchmark.

Finally, compliance doesn’t stop with your own team. Any marketing tools or platforms you use must also meet GDPR standards. Before adopting new software, verify that vendors have robust data security measures in place to avoid compliance risks down the line.

GDPR compliance for different business sizes

Businesses of all sizes operating in the EU must comply with the GDPR, but their approach to compliance will vary based on resources, data processing activities, and operational complexity.

GDPR compliance for enterprise companies

Enterprises processing large volumes of personal data must take a structured approach to GDPR compliance. This includes appointing a Data Protection Officer, conducting Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), and integrating compliance into company-wide policies and systems. Managing third-party risks is also crucial, so that all vendors meet GDPR requirements.

GDPR compliance for small businesses

Small businesses, even sole proprietors, are subject to GDPR regulations if they handle the personal data of EU residents. While they may not always need a DPO, they must still follow data protection principles, obtain valid consent, and implement security measures. Given resource constraints, leveraging automated compliance tools can help contain resource demands.

GDPR compliance for startups

Startups collecting or processing personal data must integrate data protection compliance from the beginning. This is important legally, but also, ongoing compliance is easier and less tricky than trying to retrofit it into operations that have grown substantially.

This includes designing privacy directly into products, websites, and other touchpoints, setting up consent management solutions, and ensuring secure data storage. Early adoption of compliance best practices can prevent costly legal issues and build customer trust to help a small business grow.

Assessing your GDPR compliance

Regular GDPR compliance assessments help organizations identify gaps and improve data protection practices. A structured framework like the one below can guide businesses through evaluation areas.

If you’re looking to assess your business practices to see if your processes comply with the GDPR, here are the aspects to evaluate:

- Data processing review: Determine if your business processes EU personal data and under which legal basis.

- Data collection and storage: Assess how data is collected, stored, and shared.

- Consent management: Verify that you are obtaining and documenting valid consent, and that users can easily withdraw it.

- Security measures: Evaluate the effectiveness of encryption, access controls, and incident response plans.

- Data subject rights: Establish clear processes for handling requests related to data access, correction, and deletion.

By following this structured compliance framework, your company can proactively address potential gaps and stay prepared for regulatory audits.

What are the penalties for noncompliance with the GDPR?

Failure to comply with the GDPR can result in significant fines. The regulation sets two levels of penalties:

- Up to EUR 10 million or 2 percent of annual global turnover for first-time or less severe violations, such as inadequate record-keeping or failing to notify authorities of a data breach.

- Up to EUR 20 million or 4 percent of annual global turnover for serious or repeat violations, such as unlawful data processing or failing to obtain valid consent.

Regulators also have the authority to issue warnings, impose processing bans, or require corrective actions. Businesses should prioritize compliance to avoid financial and reputational damage.

How Usercentrics can help you achieve GDPR compliance

Achieving and maintaining GDPR compliance can feel daunting, but the right tools and resources can help make the process simpler, less resource intensive, and enable better insights.

A Consent Management Platform (CMP) is one such tool that can help your company manage user consent in a structured and compliant way.

Usercentrics CMP is one such tool that enables you to collect, store, and manage consent while promoting transparency in your data collection practices.

We deliver features like cookie and tracker scanning, surfacing and providing visibility into the tracking technologies in use on your website and helping you stay aligned with GDPR requirements.

We also offer customizable privacy policies and automated reporting to further simplify compliance efforts. These features reduce the need for manual updates and help ensure ongoing adherence to the GDPR.

With Usercentrics CMP, businesses can not only meet GDPR requirements but also build trust with customers by maintaining clear and transparent data practices.

In 2019, New York’s data breach laws underwent significant changes when the SHIELD Act was signed into law. The regulation has continued to evolve, with new amendments in December 2024. This article outlines the SHIELD Act’s requirements for businesses and protecting and handling New York state residents’ private information, from security requirements to breach notifications.

What is the New York SHIELD Act?

The New York Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (New York SHIELD Act) established data breach notification and security requirements for businesses that handle the private information of New York state residents. The law updated the state’s 2005 Information Security Breach and Notification Act with expanded definitions and additional safeguards for data protection.

The New York SHIELD Act introduced several requirements to protect New York residents’ data. These include:

- a broader definition of what constitutes private information

- updated criteria for what qualifies as a security or data breach

- specific notification procedures for data breaches

- implementation of administrative, technical, and physical safeguards

- expansion of the law’s territorial scope

The law also increased penalties for noncompliance with its data security and breach notification requirements.

The New York SHIELD Act was implemented in two phases:

- breach notification requirements became effective on October 23, 2019

- data security requirements became effective on March 21, 2020

Who does the New York SHIELD Act apply to?

The New York SHIELD Act applies to any person or business that owns or licenses computerized data containing the private information of New York state residents. It applies regardless of whether the business itself is located in New York. This scope marked a significant expansion from the previous 2005 law, which only applied to businesses operating within New York state. The law’s extraterritorial reach means that organizations worldwide must comply with its requirements if they possess private information of New York residents, even if they conduct no business operations within the state.

What is a security breach under the New York SHIELD law?

The New York SHIELD Act expanded the definition of a security breach beyond the 2005 law’s limited scope. The previous law only considered unauthorized acquisition of computerized data as a security breach. The New York SHIELD Act includes the following actions that compromise the security, confidentiality, or integrity of private information:

- unauthorized access to computerized data

- acquisition without valid authorization to computerized data

The law provides specific criteria to determine unauthorized access by examining whether an unauthorized person viewed, communicated with, used, or altered the private information.

What is private information under the New York SHIELD Act?

The New York SHIELD law defines two types of information: personal and private.

Personal information includes any details that could identify a specific person, such as their name or phone number.

Under the 2005 law, private information was defined as personal information concerning a natural person combined with one or more of the following:

- Social Security number

- driver’s license number

- account numbers with security codes or passwords